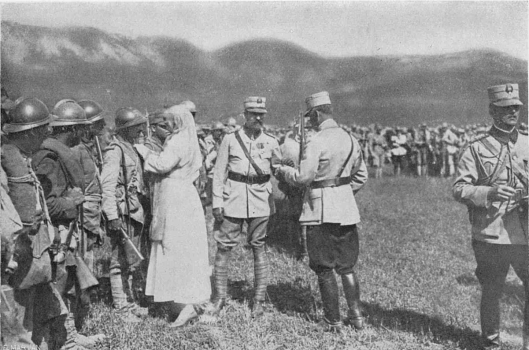

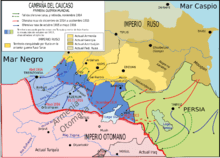

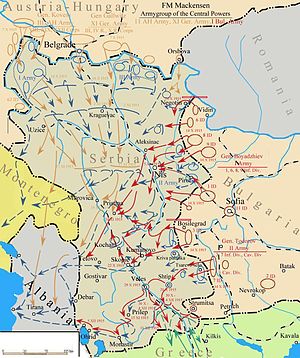

July began with the aptly named July Offensive of the Russians. It was launched by the Minister of War and de facto head of the Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky (hence also named the Kerensky Offensive), and commanded by Aleksei Brusilov of the successful Brusilov Offensive of 1916. Kerensky, determined to honor his commitment to the Allies, completely underestimated the popular desire for peace, which the Bolsheviks were demanding, and overestimated the state of the army, which was deteriorating rapidly. Brusilov was convinced a military collapse could not be avoided, but he would take a shot at a new offensive.

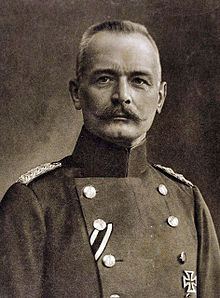

The offensive literally began with a bang, the biggest artillery barrage of the Eastern Front, which blew a hole in the Austrian lines and allowed an advance, but German resistance caused mounting Russian casualties. Morale began to crumble even more quickly, and with the exception of General Lvar Kornilov’s well-trained shock battalions, the infantry essentially stopped following orders. The advance ended completely on 16 July, and three days later came the inevitable German-Austrian counterattack, which drove the Russians back 150 miles, right into the Ukraine.

The failure of the July Offensive to a great extent doomed the Provisional Government, though the ultimate success of the Bolsheviks would depend upon a certain amount of luck. On 19 July Kerensky replaced Prince Georgy Lvov as Prime Minister and became Commander-in-Chief in August, but the handwriting on the wall was growing larger. When the July Offensive came to a halt on the 16th, soldiers and workers, demanding “all power to the Soviets,” began demonstrations in St. Petersburg and other cities, the July Days. The Bolshevik leadership was taken by surprise, but ultimately supported the movement, only to be confronted with troops loyal to the Provisional Government. The Central Committee of the Bolsheviks called off the demonstrations on 20 July, and Kerensky began a wave of arrests. Lenin narrowly escaped capture, but many other Bolsheviks, like Leon Trotsky and Grigory Zinoviev, ended up in prison.

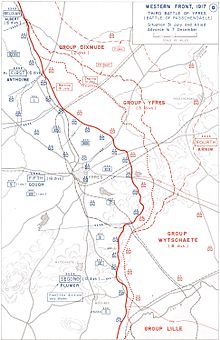

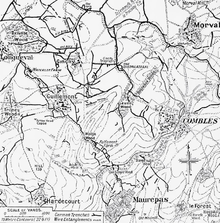

Not to be outdone, at the opposite end of the war the British launched the Battle of Pilckem Ridge on 31 July. Actually, Pilckem Ridge was the first of a series of offensives collectively called the Third Battle of Ypres (or Passchendaele), which would stretch into December and were a continuation of the Flanders Campaign begun with the Battle of Messines Ridge in June. “Wipers,” as Tommy called it, would be a four month mud bath for Commonwealth troops.

On a more romantic – and drier – note, on 6 July Colonel Lawrence and his Bedouins captured the town of Aqaba with virtually no casualties, though not quite as the movie depicted it. The real fight was on 2 July at Abu al Lasan about fifty miles northeast of Aqaba. A separate Arab force had seized a blockhouse there, but a Turkish battalion recaptured it and then killed some encamped Arabs, which outraged Auda Abu Tayi, the leader of Lawrence’s Howeitat auxiliaries. He took the town, slaughtering some 300 Turks, and local tribes flocked to him, swelling Lawrence’s force to 5000. They then moved on Aqaba, which had already been shelled by Allied naval forces, and the garrison surrendered at their arrival at the gates. Lawrence then immediately returned to Cairo, a camel ride of over 200 miles.

In miscellaneous news from July, on the 2nd the first regular merchant convoy left Virginia for Britain, and on the 7th the last daylight air raid on London took place, producing over 200 civilian casualties. On 28 July the British Army formed a Tank Corps, and on the 17th the Palace, responding to anti-German sentiment, announced that Britain was no longer under the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (from Queen Victoria’s consort Albert) but the House of Windsor. Kaiser Wilhelm, King George V’s cousin, responded that he planned to see The Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

Finally, in a very clever move, on 22 July King Rama VI of Siam (Thailand) declared war on the Central Powers. Through adroit diplomacy, playing the French and British against one another, Siam had managed to remain the only independent state in southeast Asia and saw an opportunity to strengthen its position and gain influence in the postwar world order by sending a token force to the Western Front. It would work (and Bangkok is now a favorite destination for European – and especially German – tourists).

![220px-Pobedata_nad_syrbia[1]](https://qqduckus.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/220px-pobedata_nad_syrbia1.jpg?w=640)