(I have said next to nothing about life in the trenches, and rather than spend time detailing the unimaginable environment of the Western Front, I recommend two books. Richard Holmes, Tommy (2004) is an exhaustive but delightful study of every aspect of trench life, and Ernst Jünger, Storm of Steel (In Stahlgewittern) (many editions) is the sometimes surreal memoir of a German soldier who lived through the entire war. I have discovered that my major chronological source for the war was in error regarding the Fifth Battle of the Isonzo, which began in March and not February.)

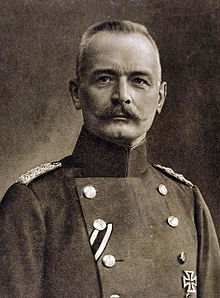

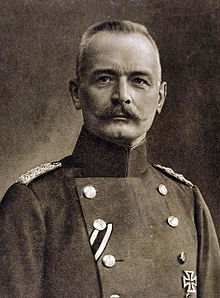

When we left Verdun at the end of February, the German offensive had stalled because of mud, and von Falkenhayn began considering whether to cancel the operation. The expectation had been that artillery could suppress the enemy guns on the west side of the Meuse, but this did not prove to be the case, and the French artillery, well-positioned on heights and behind hills, wreaked havoc among the German troops advancing along and to the east bank of the river. But the front crossed the Meuse north of Verdun, and von Falkenhayn was convinced by subordinates that a southward advance on the west side of the river could silence the French guns. General Heinrich von Gossler’s plan involved assaulting the village of Mort-Homme and Hill 265 (sounds like Vietnam) near the Meuse on 6 March and then Avocourt and Hill 305 to the west on 9 March.

Phillipe Pétain (far left)

Falkenhayn

Verdun front at the end of March

Like so many offensives on the Western Front, it did not work out that way. Despite a heavy bombardment – Hill 304 was lowered by seventeen feet – the French artillery and counterattacks slowed the advance and inflicted great casualties. Only after a week did the Germans achieve the objectives for the first day, capturing Hill 265 on 14 March. On 22 March two German divisions attacked a position near Hill 304 and were slaughtered by a rain of shells, and the offensive came to an end. By the end of the month the Germans had suffered 81,607 casualties for minimal gains, and Verdun was still French. There would be nine more months of this. The commander on the French side at this time, incidentally, was General Philippe Pétain, who would later become the head of state of the Germany puppet Vichy France (1940-44).

Elsewhere in the war, the Fifth Battle of the Isonzo began on 9 March. The Italian army in the north had been rested and refurbished, and the French were pressuring Rome for an offensive. After four failed attempts one must suspect that there was little expectation of any breakthrough, and the point of the operation was in fact to relieve the pressure on the Russians and on Verdun, though how that would happen is not at all clear, especially in the case the French at Verdun. Even General Cadorna termed the offensive a “demonstration,” which label of course made no difference to the troops, who would be just as dead when shot.

Austrian fort on the Isonzo front

Though some fighting continued to the end of the month, the battle essentially ended after only six days because of the horrible weather conditions, demonstrating once again the futility of these assaults. Despite an almost three to one advantage in men and guns the Italians could make no headway, and each side suffered just under 2000 casualties. How fine to die for your country in a pointless “demonstration.” Incidentally, the stony ground and cliffs made this front even more dangerous, since every shell impact would produce a deadly cloud of stone splinters.

Under the same pressure to take some of the heat off the Western Front on 18 March the Russians launched the Lake Naroch offensive in White Russia (Belarus). The Russians had more guns and three times as many troops as the Germans and came up with a somewhat less than novel plan: (inaccurately) shell the German positions for two days and then send bunched formations of infantry charging across the muddy ground. By the end of the operation on 30 March General Alexei Evert had gained six miles and lost 110,000 men to the Germans’ 20,000 (German estimates). The Germans promptly retook the territory.

German troops at Naroch

Russian troops at Naroch

General Alexei Evert

Meanwhile, the British troops besieged in Kut on the Tigris River had enough food to last until the middle of April, and in any case the spring rains would soon make the whole area a disease-ridden quagmire. On 8 March a relief force of some 20,000 under General Fenton Aylmer reached Dujaila, downriver from Kut, and assaulted a Turkish force half their size. But the Turks, under the command of Golz Pasha and Halil Pasha (Halil Kut, a major actor in the Armenian genocide), had fortified Dulaila well, having learned a lot about entrenchment from Gallipoli. Aylmer lost about 4000 men to Golz’s 1200 and retreated down the river. He was sacked on 12 March.

Turkish 6th army field headquarters

Halil Pasha – mass murderer

General Fenton Aylmer

Golz Pasha

In Africa General Jan Smuts, who had fought against the British in the Second Boer War, invaded German East Africa (Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania) on 5 March. With an army of over 70,000 South Africans, Indians and Africans he struck southwest from British East Africa (Kenya), while Belgian forces attacked from the west. On 10 March Smuts took back Taveta, just east of Mt. Kilimanjaro, and three days later Moshi, south of the peak. The capture of Kahe, south of Moshi, on 21 March brought an end to the operations around Kilimanjaro; the Germans had left. Lettow-Vorbeck had only 13,800 troops, mostly Askaris, and had no choice but to withdraw when faced with overwhelming numbers, something easily done given his superior mobility. The Allies would steadily capture real estate, but never Lettow-Vorbeck, and meanwhile their troops were dying of disease.

Bridge destroyed by Lettow-Vorbeck

General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck

General Jan Smuts (right)

hard to see map

The remainder of the events of March 1916 were of a political or strategic nature. True to its word, on 1 March Germany expanded its submarine warfare, ultimately bringing the United States closer to involvement in the war. On 9 March Germany declared war on Portugal, which had refused to return German steamers captured on the Tagus River in February; with even less reason Austria-Hungary also declared war six days later. Actually, inasmuch as Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) bordered on German East Africa there was indeed a point of contact between the two countries, and Lettow-Vorbeck would happily use that territory in his Great Chase with the British.

Lettow-Vorbeck

Allied interference in Persia continued, with Russian operations in the northwest and British forces – the south Persian Rifles under Sir Percy Sykes – in the south. On 25 December 1915 the Allies had “persuaded” the Shah to appoint a more pro-Entente Prime Minister, Prince Farman Farma, and now on 5 March he and his cabinet were compelled to resign for refusing to support Russian-British control of the Persian military and finances. Anglo-American meddling in Iranian affairs was just beginning.

Prince Farman Farma and Percy Sykes

More “resignations.” On 15 (?) March Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, the father of the German navy, resigned as Secretary of State of the Imperial Naval Office, having lost the support of the Kaiser and naval establishment because, ironically, of his support for unrestricted submarine warfare. More emblematic, on 29 March Alexei Polivanov, who had been struggling to reform the Russian army, resigned as the Minister of War. In August 1915 he had argued against Nicholas’ assumption of supreme command and thus alienated Alexandra, who persuaded her husband to sack him. One can hardly get choked up about the impending execution of this couple.

Empress Alexandra

Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

Alexei Polivanov

Finally, on 12 March the Allies held a conference in Chantilly to discuss the summer offensive; the outcome would be the nightmare of the Somme. And there was another conference at Paris from 26 to 28 March, the result of which was a declaration of unity among the Allied powers: Britain, France, Belgium, Portugal, Italy, Serbia (which technically did not exist at the moment), Russia and Japan. The Czar must have been delighted to have as an ally the power that had annihilated his Baltic and Far Eastern fleets a decade earlier. (Yes, Japan; I have been ignoring the relatively trivial events of the Far East and Pacific.)

*Paris in 1916