(The major post-war political arrangements would not be confirmed until the Versailles Treaty of June 1919 and the Treaty of Trianon of June 1920, but most were in the air before that.)

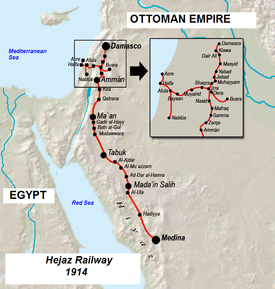

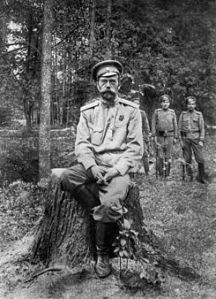

The Great War dramatically changed the map and political culture of Europe. Three large empires had collapsed: Romanov Russia, Hapsburg Austria and Ottoman Turkey. The result was the emergence of independent states in Eastern Europe, new French and British provinces in the Middle East and Africa and the general disappearance of autocratic monarchy in favor of dictatorships.

Yugoslavia, composed of the Slavic provinces of the Austrian Empire, appeared, along with Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, while the emasculation of Germany and the chaos in Russia allowed the formation of an independent Poland for the first time since the Third Partition of Poland in 1795. While the Russian Civil War raged through 1918 and 1919, Belarus, the Ukraine and several pocket states in the Caucasus asserted their independence, only to be reabsorbed into the new Russian Empire with the triumph of the Bolsheviks and establishment of the USSR. And Turkey was reduced to Anatolia and a toehold in Europe in the area surrounding Istanbul.

The German Empire was a special case. Though possessing minorities of Danes, French and especially Poles on its western and eastern frontiers, it was overwhelmingly ethnic Germans and could not “collapse” as its neighbors did. Like the former provinces of the Austrian and Russian Empires, Germany would have its frontiers redrawn along ethnic lines, according to the mandate of President Wilson. Consequently, Germany lost the northern part of Schleswig-Holstein to Denmark and Posen to Poland, which was given access to the Baltic Sea by creating a “corridor” along the Vistula River to the now “free” city of Danzig (Gdańsk). This of course separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany, a perfect recipe for future trouble.

But Germany had another problem: France. 87% of the population of Alsace-Lorraine was German-speaking (it was conquered by Louis XIV), but even President Wilson could see that the French would never accept anything less than a full restoration of the province to France. This was a question of honor, and the territory was returned to France, despite the wishes of many of the inhabitants; some French politicians even demanded the incorporation of the Rhineland into France. Altogether, Germany lost 25,000 square miles of territory and 7 million people.

French, British and Italian territorial demands apart, restructuring Eastern Europe along ethnic lines was not at all easy, given the intermingling of ethnic populations and historic claims to territory. The biggest loser was Hungary, whose frontiers were settled by the Treaty of Trianon, dictated by the Allies in 1920. The new Hungarian Republic lost 72% of the territory and 64% of the population of antebellum Kingdom of Hungary, mostly to Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia. Granted, the Kingdom had a huge non-Hungarian population, but the Treaty left 3.3 million (31%) ethnic Hungarians outside the Republic. Romania, on the other hand, was a big winner, gaining Transylvania, Bessarabia and Bukovina and thus doubling the size of the Romanian state.

Under the influence of the Allies, especially America, all these new political entities, including Germany, began their post-war existence with parliamentary governments, either as republics or limited monarchies. Like America attempting to create a democratic government in Afghanistan, this was wishful thinking on a grand scale. None of these polities had any real experience with democracy, and they were ill-equipped to deal with the turbulent 1920s. Despite the attempt to draw boundaries according to ethnic lines, there was immediately dissatisfaction with the new frontiers; old territorial claims could not so easily be discarded. A number of local wars promptly broke out, confronting the new civil governments with serious strain and threats, especially from successful military leaders.

The Versailles Treaty established an international body for Europe, the League of Nations, but such an organization was before its time and lacked the powers necessary to enforce its decisions. Even President Wilson, the major supporter of the League, could not convince an isolationist Congress to join the organization. If France and Britain were reluctant to challenge Hitler in the late 1930s, they certainly had no interest in going to war in the 1920s because of border conflicts in Eastern Europe.

There was also the looming presence of the new Soviet Empire, eager to regain czarist provinces lost during the defeat and following Civil War and ready to support communist movements throughout Europe. Unsurprisingly, the typical response was official and unofficial repression of these political groups (and ethnic minorities), leading inevitably to attacks on other political opponents and more authoritarian governments. These trends were then exacerbated by the worldwide Depression, which caused economic hardship and further destabilized society, creating more support for strong leaders who could solve problems that seemed beyond elected parliaments. And of course, a suffering population was more than ready to blame the ethnic and religious “others” in their midst.

As the leader of the defeated Central Powers and occupier of eastern France and Belgium (and for the French as the victor of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71), Germany was a special case. Much more than the other Allies, France wanted revenge, crippling reparations and the emasculation of Germany for all time to come, an approach to peace that almost guaranteed the failure of the new democratic republic. French demands could only strengthen the German far right, which was already gaining popular support in its increasingly violent struggle against the communists.

They also fanned the flames of resurgent German nationalism and the growing myth of the Dolchschoẞ (“stab in the back”), the idea that the German military did not lose the war but was betrayed by the civilian government that succeeded the Kaiser. The men who signed the Armistice and the later Treaty of Versailles were the “November criminals,” who had stabbed Germany in the back, and the anti-democratic forces, especially Hitler’s National Socialists, seized upon this nonsense to attack the Weimar government.

As a result of all these pressures, aided by the emergence of the fascist Third Reich, by the middle 1930s only two states in Central and Eastern Europe possessed functioning democratic governments: Finland and Czechoslovakia (despite its multi-ethnic population). Germany, Austria, Italy, Romania, Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Russia all had authoritarian governments. And Europe was again on the brink of war.

The Great War also altered the cultural landscape of Europe, essentially eliminating courts and royalty as well as the last continental empires. The sense of European peace and security that had existed since the fall of Napoleon evaporated, replaced by a growing nervousness as Europe left centuries of tradition behind. The shock that the Great War delivered to European civilization can hardly be overestimated; as F. Scott Fitzgerald would later say in Tender Is the Night, “All my lovely beautiful safe world blew itself up.” Coincidentally, the emergence in the early years of the twentieth century of relativity and quantum physics shattered the well understood and orderly universe of classical physics, dragging science itself into the brave new world of confusion and uncertainty created by the Great War.

The roots of the Second World War are clearly found in the Great War and its immediate aftermath. The Treaty of Versailles, especially the financial demands, almost guaranteed that the Weimar Republic would not survive, at least not as a democratic entity. The Bolshevik Revolution and emergence of the Soviet Union threatened Eastern Europe and helped fuel the rearmament of Germany, which under Hitler was increasingly focused on the east. And when the crisis approached in the late 1930s, the horrific losses of the Great War certainly contributed to the inclination towards appeasement rather than early and robust action against Hitler. The First and Second World Wars might be viewed as a single war with a twenty year pause, a European civil war that ended with two non-European powers, the USSR and the USA dominating the continent.

Incidentally, on 3 October 2010 Germany paid off the last of the Great War reparations.