The Flavian dynasty came to an end with Domitian’s death, but circumstances conspired to prevent a repeat of 68. The Senatorial conspirators had their own candidate ready, a respected sixty-year old Senator, M. Cocceius Nerva, who was far more careful than Galba. He had the actual murderers of Domitian executed and adopted as his heir the popular general M. Ulpius Trajanus, whom he made co-ruler. So well trained was the military by the Flavians that these measures were enough to secure their acquiescence to the assassination of Domitian. Nerva, who died in 98, was in some ways the Gerald Ford of the Principate, keeping the imperial seat warm for a military leader acceptable to the legions. His important achievement was preventing another civil war and inaugurating a period of excellent government, the apogee of the Empire, the age of the Five Good Emperors, of whom Nerva was the first.

Trajan was the great warrior Princeps, violating the dictum of Augustus and dramatically extending the Empire. The Dacian Wars made strategic sense, eliminating the centuries old Dacian kingdom, which under Decebalus had been engaged in constant raiding across the Danube. The two Dacian provinces he created (the heart of present-day Romania) were rich in gold and fairly easily defended in normal times; they were abandoned during the Anarchy.

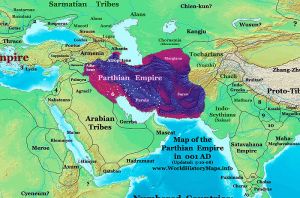

His attempt to find a final solution to the problem of the Parthian Empire, an irritant rather than a serious threat on Rome’s eastern frontier, is far less easy to defend. Their rich western territories, essentially Mesopotamia, were easily conquered, but the Parthians simply fled east to Iran. By the time Trajan reached the head of the Persian Gulf, revolt was already erupting behind him. The problem was not conquest; it was occupation. The area already possessed a millennia old non-classical civilization that could not be easily assimilated, as were the Hellenized eastern provinces or the barbarian western. This meant extensive internal occupation would be required, and the Roman military simply did not have the manpower to secure these new provinces. Trajan died suddenly of a stroke in 117 and was subsequently remembered as the Optimus Princeps for his excellent administration and relations with the Senate and his stirring conquests.

It was reported that on his deathbed that the childless Trajan had adopted his nearest male relative, a second cousin, P. Aelius Hadrianus, and while this may be untrue, the army accepted it. Trajan had cultivated good relations with the Senate, dispelling the ill will of the Flavian era, and Hadrian attempted to follow his example, actually requesting that the Senate approve his nomination as Princeps, which of course they had little choice but to do. He returned to a defensive policy, wisely abandoning Trajan’s eastern conquests, a very bold and less than popular move for a Roman emperor. He wanted to evacuate Dacia as well, but sensed that popular opinion would not tolerate this. Otherwise, Hadrian was the great peripatetic Princeps, constantly touring the Empire to insure that the military, essentially a garrison force, maintained a high standard of efficiency. And to see the sights – he was also the great tourist Princeps, especially taken by anything Greek, which may account for his wearing a beard, which became the fashion for subsequent emperors.

The one great tragedy of Hadrian’s reign was the Second Jewish Revolt, which could possibly have been prevented. Diaspora Jews were already causing serious trouble before Trajan’s death, and Hadrian, in a rare instance of inept policy, decided to rebuild the ruined city of Jerusalem as a purely gentile settlement with a temple of Jupiter where the Jewish temple had once stood. The result was a revolt that took the Romans three years to crush and devastated Judea, killing several hundred thousand people, both Jews and non-Jews.

Hadrian died in 138, apparently from tuberculosis. His adopted heir was the Senator T. Aurelius Fulvus Boionius Arrius Antoninus, who gained the cognomen Pius for convincing a Senate hostile to Hadrian to deify him. To secure long term stability Hadrian also compelled Antoninus to adopt his own nephew, the seventeen year old M. Annius Verus, and curiously, also the seven year old L. Ceionius Commodus, whose father, also L. Ceionius Commodus, was his first choice, now dead. Antoninus’ reign was essentially peaceful and his relations with the Senate excellent, and when he died in 161, he was succeeded by his well-trained nephew, known now as M. Aelius Aurelius Verus.

Upon his succession Aelius took the name M. Aurelius Antoninus and made L. Ceionius his colleague under the name L. Verus Commodus. This was the first time the Empire had actual co-rulers, but fortunately for Rome the indolent Verus died in 169, leaving Aurelius sole Princeps. In 177 his natural son, M. Commodus Antoninus, became co-emperor and obvious heir, a decision that would prove to be disastrous for the Empire.

It can be said that the decline of the Roman Empire began with the reign of Marcus Aurelius, perhaps ironically, given his character and dedication. He was the great Stoic emperor, in many ways the philosopher ruler that Plato had dreamed of. Possessing a fine intellect, he was early on attracted to Stoic philosophy and almost certainly would have preferred to spend his life in conversation with his friends rather than shouldering the burden of rule. But he was a citizen of the cosmopolis, the world polis, which Roman Stoics, with some justification, had identified with the Roman Empire.

Greek Stoicism had sought apathē, a state of emotional equilibrium in which the individual was disturbed by neither bad nor good developments. This naturally inclined the Stoic to withdraw from the disturbances of the world, but the Roman character could not accept such rejection of duty, and Roman Stoics, prominent among the Senatorial elites, felt the need to serve. And Aurelius was not just a citizen of the cosmopolis, but designated to become the First Citizen, a duty he could not refuse.

And that duty was onerous. In 161 the Parthians invaded Armenia and Syria, and after some setbacks – the eastern legions were never as tough as the northern – they were repulsed and Parthia was invaded. By 166 the Parthians were defeated and their capital, Ctesiphon, destroyed, leaving them quiet for the next thirty years. Unfortunately, the returning troops brought with them the “Antonine plague,” probably smallpox, which rapidly spread across the Empire, leaving entire districts depopulated, and it may have been the cause of Verus’ death in 169.

The removal of so many northern units for the Parthian War encouraged barbarian tribes north of the Danube, themselves under pressure from Germans in central Europe, to cross the river. The north central provinces were over run, and one group crossed the Alps and besieged Aquileia, the first time barbarians had entered Italy in almost three hundred years. The barbarians cleared out, but the storm soon broke again, and one group, the Costoboci, penetrated as far as Athens. Aurelius spent most of his remaining years on the Danube frontier fighting the Marcommani, Iazges and Quadi and was apparently on the verge of thoroughly pacifying the districts north of the river when he died in 180.

Marcus Aurelius is virtually unique among heads of state in western history in that we are able to peer into his very soul. He was accustomed to jot down his innermost thoughts, and these writings were preserved and published as the Meditations, apparently contrary to his intentions. What we see is a man who was compelled to perform his duty to the Empire, but who did so with a kind of detachment, spending those long years fighting on the Danube frontier yet believing that in the end none of it really mattered. Life was transient, fleeting, as he eloquently puts it: “Yesterday a drop of semen, tomorrow a handful of spice and ashes.” He was, in short, the noblest man to rule the Empire.

The imperial situation had been restored, but the Empire was still in dire straits, short of money and manpower from the plague and constant warfare. Had it not been for the attention paid to the military establishment by his predecessors and Aurelius’ diligence in dealing with the growing barbarian tide, the Empire might actually have begun collapsing. Even a competent successor would have faced serious problems, and unfortunately Rome was left in the hands of a seriously incompetent ruler, Aurelius’ son, M. Commodus Antoninus, who had been made co-emperor in 177.

Why Aurelius allowed his unpromising son to succeed him is something of a mystery, and there is evidence that at his end he realized his mistake, too late. Commodus, who was with his father in the north, promptly made peace with tribes, undoing much of his father’s work, in order to return to the pleasures of Rome. Commodus was corrupt, indolent and brutal and preferred to leave the government of the Empire at this critical time to a succession of favorites, who unlike Pallas and Narcissus under Claudius were far less interested in the state than their own power. (One is perhaps reminded of the American Congress.) Unsurprisingly, he did not get along with the Senate and executions abounded, while he indulged himself fighting as a gladiator in the arena, a slap in the face of Roman dignity. By 191 he seems to have become completely deranged, playing the role of Hercules and renaming Rome Colonia Commodiana. Meanwhile, the Senatorial class was decimated and the treasuries empty, despite the practice of selling state offices, and the Empire was surviving because of the diligence of his commanders. His favorites saw the handwriting on the wall, and on the last day of 192 he was strangled, and his memory was damned.

Commodus’ assassination was followed by a replay of the Year of the Four Emperors, this time on a larger and more destructive scale. The conspirators selected a respected army commander, P. Helvius Pertinax, but although the Praetorians initially accepted him, they really did not trust him, especially when he paid only half the promised bribe. He lasted three months before he was murdered, and the Guard, at a loss for a candidate, auctioned off the Empire to the highest bidder, a rich Senator named M. Didius Julianus. This humiliating moment in the history of the Principate angered everyone, and Julianus’ days were numbered in any case. Once news of the death of Pertinax had reached the headquarters of the Danubian army, the troops had proclaimed L. Septimius Severus emperor, and he was already marching on Rome. Septimius promised the Praetorians their lives if they abandoned Julianus, and he was murdered on the first of June 193.

Thus began the last dynasty of the Principate. Septimius disbanded the Praetorian Guard and created it anew, this time with veterans from outside Italy, and soon after he stationed a legion in Italy. Meanwhile, a challenger, C. Perscennius Niger Justus, former general and present governor of Syria, was proclaimed emperor by his troops, and Septimius marched east and defeated him in 194. Septimius then invaded Parthia, and though successful, he was soon called back west to face another challenger, D. Clodius Albinus. Septimius had made Albinus, the governor of Britain, his “Caesar,” a sign that he was to be the successor, but in 195 or 196 he was proclaimed emperor by his forces, probably because he feared betrayal by Septimius. He was defeated in 197, and Septimius returned to the east, where by 199 he had chased the Parthian king east and created a province of Mesopotamia. He died in 212, fighting Caledonians in Britain.

According to his wish, Septimius’ sons, M. Aurelius Antoninus Caracallus and P. Septimius Geta, became co-rulers, but they already hated one another, and Caracalla had his younger brother murdered in 212. Caracalla, though cruel and cowardly and lacking in any charm, understood the importance of keeping the army happy, and while he had no particular military talents, he did useful work on the northern frontiers. Pursuing his dream of becoming a second Alexander the Great, in 216 he invaded Parthia and occupied northern Mesopotamia without encountering any resistance. In the spring of the following year, however, he was assassinated on the orders of his Praetorian Prefect, M. Opellius Macrinus, who himself feared that Caracalla was about to arrest him. Two days later Macrinus was proclaimed emperor by the army.

Foreshadowing the Anarchy, Macrinus was the first emperor who was not of the Senatorial order. He was initially not unpopular after the vindictive tyranny of Caracalla, but though without vices, he was also lacking in any talent, and he alienated his troops by buying peace from the Parthians and keeping his northern legions in Syria. Meanwhile, the Severan family was not idle. Caracalla’s aunt, Julia Maesa, had two grandsons, and she put it about that the elder, Bassianus, was the natural son of Caracalla, and this along with the now customary bribe caused the nearest legion to proclaim him emperor in 218. Troops began deserting to Bassianus, and soon defeated, Macrinus and his son and co-emperor, Diadumenianus, were killed. Thus began the reign of easily the most worthless man ever to rule the Emperor.

The fifteen year old Bassianus officially took the name M. Aurelius Antoninus, but as chief priest of an orgiastic Syrian deity, he had adopted the name of his god, Elagabalus. His obsession with this alien religion, shared by his mother Julia Soaemias, quickly led to disaster. He made Elagabalus chief god of Rome, engaged in rites such as ritual prostitution and cross-dressing and even married one of the Vestal Virgins. Depravity became the means of access to high office. Everyone was disgusted, and fearing for her own position, his grandmother convinced Elagabalus in 221 to adopt her other grandson, the thirteen year old Alexanius, a youth of entirely different character. In 222 Alexander’s mother Julia Mammaea bribed the already resentful Praetorians to murder Elagabalus and his mother, who were dragged through the streets and thrown in the Tiber.

M. Aurelius Severus Alexander became the last Princeps, if that term may still be applied. In effect the government was run by his grandmother and after her death his mother, and although their administration saw a return of respect for the Senate and some economic revival in the Empire, the soldiery grew impatient with the unwarlike Alexander. In 227 the Sassanid Persian dynasty put an end to the exhausted Parthian Empire and occupied the Roman province of Mesopotamia, and in 231 Alexander invaded the new Persian Empire, but failed to recover Mesopotamia. In 234 he responded to German incursions across the Rhine and Danube by concentrating an army near Mainz, but he first attempted to buy off the barbarians, perhaps influenced by his mother, who was present. The disgusted northern legions murdered him and his mother in 235 and proclaimed C. Julius Verus Maximinus, a one-time Thracian peasant who had risen through the ranks, emperor. The Anarchy had begun.

Politically, things had certainly changed. By 235 the Senate had become a virtually powerless institution, no longer proposing decrees and no longer having any control over the magistracies and governmental appointments. Its only power was to grant or withhold deification of a dead emperor, and that was constrained by the whims of the new ruler. Further, less and less did the Senate represent the old Roman noble families. It was not simply new Italian families, such as the Flavians, but increasingly also provincial nobility, a process that went all the way back to Caesar.

This growing cosmopolitanism was also reflected in the Princeps and the Empire as a whole. Trajan and Hadrian were Spaniards and Septimius Severus from north Africa, as Roman as Caesar but without the pure bloodlines of the old families. This “democratization” ultimately extended to even the lowest: in 212 Caracalla granted the Roman citizenship to virtually every free male in the Empire – the so-called Antonine Constitution. Caracalla did this in order to increase revenues and the citizenship had become essentially politically meaningless, but it represents something virtually unique in the history of empire. A man whose ancestors had painted themselves blue and fought the legions now had the same legal status as one who could trace his line back to the early Republic. This enfranchisement of the Empire, together with Septimius’ stationing of a legion in Italy, paved the way for the ultimate evolution of Italy into just another set of provinces.

This “democratization” was also impacting the military. Traditionally, the officer class came from the Senatorial nobility, and the highest a ranker might rise to was chief centurion, the Roman equivalent of Sergeant-Major. This barrier was already crumbling as emperors made increasing use of the Equestrian class for commands and high posts (the lesser nobility, traditionally involved in business and lower administrative posts), further marginalizing the Senate. Septimius dramatically increased the opportunities for rankers and especially their sons to gain Equestrian and even Senatorial status, thus opening the way for the highest offices, including Princeps, as Maximinus demonstrates. The replacement of the traditional soldiers’ cult of the legionary standards with a sort of emperor worship is a sign of the increasingly intimate relationship between army and ruler. In fact, veterans had become a favored class in the state, enjoying many special privileges; this is the “militarization” of the Empire.

Military pay had risen steadily and donatives by newly elevated emperors were now the common practice, but the army remained an efficient and disciplined force. Frontier fortifications were becoming more common – Hadrian built a wall from the Tyne to the Solway Firth and further north Antoninus constructed an earthen rampart and ditch from the Forth to the Clyde – but the legions remained a field army, ready to be moved to any critical spot, and a point defense remained the grand strategy of the Empire. The provincial auxiliaries had become virtually identical to the legions, especially in the wake of the Antonine Constitution, and were very Romanized, but the practice of creating numeri, cheaper but thinly Romanized native and even barbarian units on the frontiers, was a growing threat to imperial stability. Finally, Parthia and subsequently Persia was becoming an imperial obsession and drain on resources, as lower quality rulers sought to emulate Alexander the Great.

One might include the period after the assassination of Commodus in the Anarchy, but while the Severans are certainly a sort of Coming Attractions for the Anarchy, they are still substantially different from what will follow. They do present a relatively stable, if weak, dynasty lasting forty-two years (compared to the twenty-seven of the Flavians), and the military has not yet declined into an inefficient and completely undisciplined mass, supporting whomever will make their lives easier, Empire be damned. The idea of a Princeps working in partnership with the Senate has of course atrophied into an all-powerful emperor, backed by the army, dealing with a virtually powerless institution. But the idea is still there, if now completely at the whim of the autocrat. It disappears completely during the Anarchy, and the emperor of the Late Empire is no longer a First Citizen but a Dominus or Lord, answering only to himself and soon enough, the Christian god.

96-180 The Five Good Emperors

96-98 Nerva

98-117 Trajan

101-102 First Dacian War

105-106 Second Dacian War

114-117 Parthian War

117-138 Hadrian

132-135 Second Jewish Revolt

138-161 Antoninus Pius

161-180 Marcus Aurelius

161-169 Lucius Verus

177-180 Commodus

161-166 Parthian War

167-175, 177-180 Danubian barbarian wars

180-192 Commodus

193 Jan-March Pertinax

193 March-June Didius Julianus

193-235 Severans

193-211 Septimius Severus

194 Defeat of Perscennius Niger

195, 197-199 Parthian war

197 Defeat of Clodius Albinus

211-217 Caracalla

211-212 Geta

212 Antoninian Constitution

214 ParthianWar

(217-218 Macrinus [and Diadumenianus])

218-222 Elagabalus

222-235 Severus Alexander

227 Sassanid Persians replace Parthians

230-233 Persian War

235 – 285 Anarchy

285 – 5th Century Dominate or Late Empire