When the Great War ended in November 1918 the Russian Civil War had already begun, and the Reds were losing. By the beginning of 1919 the entire northern Caucasus was dominated by the Whites under General Anton Denikin, while the Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia had become independent. Northwestern Russia was still in the hands of the Allies, and White General Nikolai Yudenich had begun organizing an army in Estonia. Siberia and the far east were controlled by the Allies, the Czech Legion and sundry White forces coalescing under Admiral Alexander Kolchak, who proclaimed himself Supreme Rule of Russia. The low point for the Bolsheviks came in June 1919, when General Pyotr Wrangel took Tsaritsyn (later Stalingrad) on the Volga River, only 200 miles from Moscow.

Close to crushing Bolshevism

What was the problem? Well, the emerging Marxism-Leninism ideology and its repressive methods were not at all the popular, especially among the peasantry, who wanted their own land and could hardly understand the proffered benefits of communism. As the Civil War developed, the violent repression of the Bolsheviks seemed, if anything, worse than that of the Czar, and the confiscation of food supplies for the Red Army created man-made famines that understandably dampened any peasant enthusiasm. Men like Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin were not inclined to judicial process or mercy; threats and summary executions were the way to solve any problems.

Further, the Red Army was initially hardly a first class military force, despite the efforts of War Commissar Leon Trotsky (assassinated in 1940). Workers could not be turned into effective soldiers overnight, and in any case many of the “recruits” were dragooned, essentially facing a choice of joining the cause or being shot. Such men were hardly enthusiastic about fighting, especially when death threatened, and given the growing propensity on both sides to simply slaughter prisoners, surrender was hardly attractive. The result was predictable: indiscipline, mutinies, desertions and flight in the face of the enemy.

Trotsky

The Bolshevik leadership of course saw this as the essential reason why the Reds were losing battles, and the solution was of course obvious: more terror. In December of 1917 Lenin had created the All-Russia Extraordinary Commission to Combat Counter-revolution and Sabotage – the Cheka (forerunner of the OGPU, NKVD and KGB) – a merciless secret police to eliminate political opposition, and in 1918 Trotsky organized the Special Punitive Department of the Cheka. These were detachments that followed the Red Army and set up tribunals to judge soldiers, including officers (and the odd political commissar), accused of retreating, deserting or not showing enough enthusiasm. Summary execution was very frequently the result.

Cheka on parade

Cheka at work

Even these draconian measures could not fully do the job, and in August 1918 Trotsky had the Cheka begin creating the notorious “barrier” or “blocking” troops, whose job was to shoot soldiers who retreated without orders, which generally meant just retreating, orders or not. These were men from reliable Red Army units, but the Cheka was also building up its own paramilitary forces, which would swell to over 200,000 by 1921. This was the beginning of the “Red Terror” (better, the “First Red Terror”), which by the end of the Civil War had executed anywhere from 100,000 to 200,000 (conservative estimates) people.

The Red Terror, under the leadership of the head of the Cheka, “Iron” Felix Dzerzhinsky, established the basic mechanisms – intimidation, torture, extrajudicial executions and a degree of arbitrariness – that would characterize the security apparatus of the Soviet Union. This was deemed necessary for the dictatorship of the proletariat to survive and was supported and justified by the ideology of the Bolshevik leadership: “To overcome our enemies we must have our own socialist militarism. We must carry along with us 90 million out of the 100 million of Soviet Russia’s population. As for the rest, we have nothing to say to them. They must be annihilated.” – Grigory Zinoviev (executed in 1936). And even those committed to the Bolshevik cause were not safe: “Do not look in materials you have gathered for evidence that a suspect acted or spoke against the Soviet authorities. The first question you should ask him is what class he belongs to, what is his origin, education, profession. These questions should determine his fate. This is the essence of the Red Terror.” – Martin Latsis (executed in 1937).

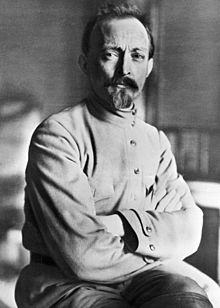

Iron Felix

Latsis

Zinoviev

Incidentally, a 15 ton statue of Dzerzhinsky was erected in 1958 in front of the Lubyanka, notorious home of the Soviet security apparatus from the Cheka to the KGB (and now of one of the directorates of the FSB, the current version of the Cheka). It was torn down when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, but a recent poll (2013) revealed that 45% of Russians want the statue re-erected. Stalin would approve.

Felix before the Lubyanka

But the tide was turning. The White forces were generally as ruthless as the Reds, and their initial popularity quickly began to drain away. It also became clear that the major figures – Denikin, Yudenich, Kolchak, Wrangel – were not so much fighting for the restoration of the monarchy as for personal power. Further, the Red Army had the advantage of a central command and inside lines of communication, while the White armies essentially fought independently. And the Allies were leaving, as resurgent American isolationism and British war-weariness and near bankruptcy took hold; by the end of 1919 all significant Allied forces had left, except the Japanese, whose remaining forces were not withdrawn until 1925.

By the middle of summer 1919 the Red Army was larger than the White and capable commanders, like Mikhail Tukhachevsky (executed in 1937), were emerging and taking the offensive. On 14 October Tukhachevsky launched a counteroffensive after defeating the last White offensive on the eastern front and captured Omsk on 14 November. Kolchak’s forces began to disintegrate, and he surrendered his command to Ataman Grigory Semyonov (executed in 1946), who held the area east of Lake Baikal with Japanese support. The Japanese, however, began leaving in July 1920, and by September 1921 the remnants of Semyonov’s army, now little more than bandits, withdrew.

Kolchak’s retreat

Kolchak

Tukhachevsky

Semyonov

With Kolchak’s army crumbling the Reds could concentrate on the south, and an alliance was made with the anarcho-communist Free Territory of Nestor Makhno in the Ukraine. Denikin’s army was soon in full retreat back to the Don River, and in March 1920 an attempt was made to evacuate the troops across the Kerch Straights to the Crimea. It was a disaster. Only 40,000 of Denikin’s men made it across, leaving behind their horses, heavy equipment and 20,000 comrades to the Reds. Denikin surrendered his command to Wrangel, who reorganized the army in the Crimea and invaded the southern Ukraine in October.

Denikin’s evacuation

Denikin

Wrangel

The Reds appealed once again to Makhno, despite the fact that they had been attempting to assassinate him, and Ukrainian troops aided in the defeat of Wrangel in November. Less than two weeks later Makhno’s staff and subordinate commanders were arrested at a conference in Moscow and executed. Makhno escaped, but the Red Army and Cheka forces descended on the Free Territory with a vengeance, conducting a massacre of anarchists; Makhno carried on a guerilla campaign until August 1921, when he and a few men fled into exile. Wrangel, meanwhile, was unable to defend the Crimea, but he was able to evacuate all his people from Russia by November 1920.

The Free Territory

Makhno

The threat in the west was the new Polish Republic, where head of state Józef Piłsudski was seeking to extend Poland’s frontiers east into Belarus and the Ukraine. After sporadic fighting throughout 1919 he launched a major offensive on 24 April 1920 and was immediately met by a Russian counterattack that drove the Poles back to Warsaw. But in August they destroyed the Red force, and the Russians accepted a cease fire in October. On 18 March 1921 the Treaty of Riga awarded Poland large chunks of Belarus and the Ukraine; the rest was absorbed by emerging Soviet Union.

Piłsudski

Finally, in the northwest Yudenich, having guaranteed the independence of Estonia, launched in October 1919 an Allied-supported offensive aimed at capturing St. Petersburg. They easily reached the approaches to the city on 19 October, but Trotsky refused to surrender the birthplace of Bolshevism, arming the workers and rushing troops from Moscow. Soon facing three times the original number of defenders and dwindling supplies, Yudenich retreated to Estonia.

Yudenich

By the beginning of 1921 it was clear the Reds had won the war and now controlled most of the former Russian Empire, but troubles remained. The Russian economy had essentially collapsed (only 20% of the pre-war level), and requisitioning of food supplies by both sides, coupled with droughts, brought on the famine of 1921-22, which killed anywhere from two to ten million. The result was endless peasant revolts, which were crushed with what was now the standard brutality; in March 1921 in sympathy with striking workers in St. Petersburg the garrison of the Kronstadt fortress revolted and was promptly overwhelmed by 60,000 troops under Tukhachevsky. The Civil War offically ended in June 1923, but minor resistance continued into the 30s.

Famine

Famine

The human cost of the Civil War is impossible to determine with any accuracy, but by any estimate it was staggering. The White Terror killed some 300,000, including 100,000 Jews, while the Reds killed or deported 300,000-500,000 Cossacks. Perhaps 1-1.5 million combatants died in battle and captivity or from disease, and 7-8 million civilians perished in massacres and from starvation and disease; in 1920 some 3 million died of typhus alone. By 1922 there were perhaps 7 million homeless “street children,” dramatically revealing the extent of the carnage.

Street children

On 30 December 1922 the Bolshevik controlled republics – Russia, Belarus, Ukraine and Transcaucasia – signed a treaty establishing the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. By 1940 there would be 15 Republics, and as of 26 December 1991 there would be none. The de facto ruler of the new USSR was Vladimir Lenin, who was ruthless enough, but he died of a stroke in 1924 and Joseph Stalin took over and began eliminating all opposition and turning the workers’ paradise into a charnel house. Forced collectivization and rapid industrialization, for example, resulted in the man made Famine of 1932-1933, which left 7-8 million dead, and in just the two years 1937-1938 as many as a million people were executed. By Stalin’s death in 1953 anywhere from 20 to 30 million souls had perished due to his policies.

Lenin and Stalin 1922

The treaty creating the USSR

The face of evil