On the Western Front the Reichswehr continued its withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line, the troops in the Somme sector beginning their retreat (called a “retrograde redeployment” by the US military) on 14 March. Allied forces began occupying the abandoned positions on the 17th, and by 5 April the Germans had completed an orderly withdrawal to their new defensive positions.

In other news from the west, on 12 March the US announced it would begin arming merchant vessels, and on 31 March the Austrian Emperor, Karl I, apparently seeing the handwriting on the wall, dispatched a secret peace proposal to the French. The French, meanwhile, were undergoing a political shakeup: Minister for War, Hubert Lyautey, resigned on 15 March, bringing down the government of Premier Aristide Briand (formed October 1915) five days later. Alexander Ribot formed a new government, just in time to confront the mutiny of half the French army.

Further east the British were beginning to put the kybosh on the Turks. On 11 March, having outmaneuvered the enemy in crossing the Diyala River, General Maude marched into an abandoned Baghdad and issued a proclamation declaring “our armies do not come into your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators”. Well, more likely as liberators of Iraqi oil.

To the southeast, however, the British Palestine campaign got off to a rocky start. On 26 March Gaza City was attacked, but a resolute defense by General Kress von Kressenstein (remember him?) and the threat of Ottoman reinforcements from the north forced them to withdraw, ending the First Battle of Gaza the following day.

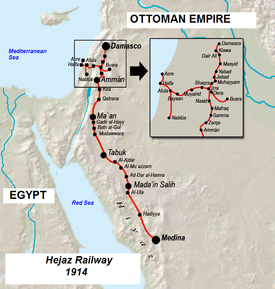

The loss at Gaza and rumors of a Turkish withdrawal from the Hejaz turned more British attention on the Arab Revolt. As it happened, rather than using the Hejaz forces to defend Palestine the Turks determined for religious reasons to defend Medina, but the Allies were reluctant to give the Arabs the heavy weapons necessary to take Medina, fearing Arab possession of the city might stir a degree of Arab unity inconvenient for Allied post-war plans. The decision was to isolate the Medina garrison and prevent any orderly withdrawal north by more concentrated attacks on the Turkish lifeline, the Hejaz Railway.

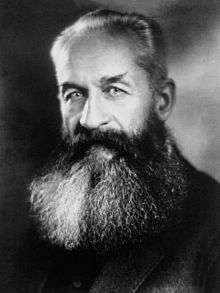

The Arab irregulars were perfect for this sort of work, and the British had the explosives and expertise to make them more effective. A demolition school had been set up at Wejh by Captain Stewart Newcombe and Major Herbert Garland, who had already developed the Garland Grenade and the Garland Trench Mortar. Together with a Lieutenant Hornby (no bio found), they began in March a serious campaign against the railroad, destroying bridges and miles of track and derailing and looting trains.

Garland, who could speak Arabic, was a particularly enthusiastic participant and personally taught Lawrence about explosives, later receiving effusive praise from his better known colleague in his semi-autobiographical Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Garland is thought by some to be the first to derail a train, probably in March, with explosives – the Garland Mine, of course.

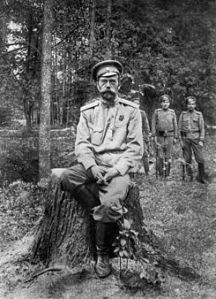

Finally, Russia. Throughout March Czar Nicolas’ troops were capturing cities in northwestern Persia (hardly a difficult task), including Hamadan, but time was running out for the Autocrat of All the Russias.

Speaking of time, dating Russian affairs before 1918 can be very confusing inasmuch as Russia still employed the Julian calendar [C. Julius Caesar 46 BC] while the West had long before adopted the more accurate Gregorian [Pope Gregory XIII AD 1582]. I have been using the Gregorian, which in the period from 17 February 1900 to 15 February 2099 is thirteen days ahead of the Julian. The Bolsheviks did not make the switch until early 1918, so the February Revolution actually happened in March and the October Revolution in November 1917.

On 3 March the workers of the Putilov machine works in St. Petersburg, fed up with the war, the incompetent autocracy and the increasing food shortages, went on strike, and on the 8th they were joined by thousands of angry women, who began recruiting strikers from other factories. The “February” Revolution had begun. And the Czar? He had left for the front the previous day.

By 10 March there were a quarter million workers in the streets, and virtually all industry had been shut down in the city. More ominous, calls for abolition of the monarchy were being heard and some soldiers were seen in the protesting crowds, and the Czar ordered the commander of the Petrograd military district, Sergei Khabalov, to disperse the strikers with force. Indecisive and inexperienced, Khabalov was not up to the job. On 11 March elements of the city garrison revolted and began firing on the police; they were disarmed by loyal troops, but government control was rapidly crumbling.

On 12 March the Czar responded to a desperate request from the Duma, Russia’s generally ineffective parliament, by questioning the seriousness of the situation, and as if in reply, the Volynsky Life Guards Regiment revolted the same day, followed by four other regiments, including the Preobrazhensky. By the end of the day some 60,000 troops in St. Petersburg were in open revolt and distributing arms to the workers, while most of their officers went into hiding.

To make matters worse – if possible – that morning the Czar had prorogued the Duma, rendering it powerless to act. Led by Mikhail Rodzianko, a number of the delegates then created the Provisional Committee of the State Duma, which proclaimed itself to be the legitimate government of the Empire. Unfortunately for them, the various socialist factions had other ideas and at the same time resurrected the Petrograd Soviet of the failed 1905 Revolution, immediately attracting massive support among the workers and soldiers. On 13 March the few remaining loyal troops in the city abandoned the Czar.

That very day Nicholas decided to return to the capital, but unable to enter St. Petersburg he ended up in Pskov, over a hundred miles to the west, on 14 March. There he was visited by Army Chief Nikolai Ruzsky and two Duma members, who urged him to give up the throne, and the following day he and his son, Alexei, abdicated. Nicholas chose as his successor his brother Grand Duke Michael, but the Grand Duke did not need a weatherman to see which way the wind was blowing and refused. The 300 year old Romanov dynasty and the Russian monarchy itself were at an end.

On 22 March Nicholas Romanov joined his family at Tsarskoya Selo, where they were confined in the Alexander Palace and protected by the Provisional Government, now under the Chairmanship of Prince Georgy Lvov. The Allies, desperate to keep Russia in the war, were prompt in recognizing the new regime: Britain and America (on the verge of war) on the 22nd and France and Italy two days later.

Germany, anxious to get Russia out of the war, took a different step and provided a train to transport the leaders of the Bolsheviks, the most extreme socialist party, from their exile in Switzerland to St. Petersburg. On 21 March Vladimir Ulyanov, aka Vladimir Lenin, arrived at the Finland Station, to be greeted by supporters singing La Marseillaise. And while the Bolsheviks would indeed take Russia out of the war, they would also lead the rodina into decades of terror and oppression undreamed of under the Romanovs.

Unknown to the Second Reich, however, the day before Mr. Ulyanov arrived in St. Petersburg President Wilson’s cabinet voted unanimously to ask for a declaration of war against Germany.