(There seems to be some confusion as to exactly when the Battle of Lake Naroch actually ended: 30 March or 16 April or 30 April? It appears the Russian infantry offensive ended around 30 March but shelling and then the German counterattack extended perhaps to the end of April.)

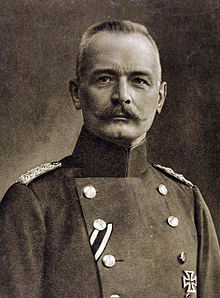

Most of the action in April 1916 took place in or concerned the east, but of course the slaughter continued at Verdun, though barely worthy of comment in a war awash in blood. When we left the “World Blood Pump,” as German propaganda put it, Falkenhayn was of a mind to give it up, but many of his commanders were convinced the French were on the verge of collapse. On 4 April Falkenhayn agreed to continue the offensive on both sides of the Meuse, but stipulated that if the assault on the east side did not reach the Meuse Heights, it would be ended.

The Blood Pump of

Verdun

Verdun-sur-Meuse

Verdun front at the end of March

Though the idea behind the offensive was to inflict unsustainable casualties on the French, Falkenhayn was becoming increasingly concerned about his own losses. He decided upon a more cautious advance, employing Stoẞtruppen, “storm troop” units made up of two squads of infantry and one of engineers and equipped with grenades, mortars, flame throwers and machine guns. They would lead the way after the artillery barrage, advancing carefully and either capturing strongpoints or isolating and identifying them for the regular infantry to deal with.

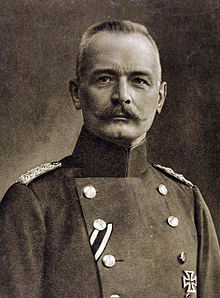

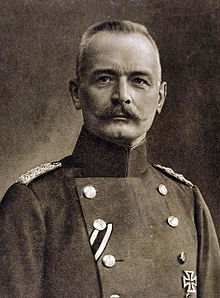

This approach did reduce casualties, but it also seriously slowed the rate of advance and was opposed by many of his generals, who of course had nothing to lose. Further, the battlegrounds had been so blasted by earlier shelling that it was difficult to find cover and construct new defenses before which the French would die in the expected counterattack. On 20 April Konstantin Schmidt von Knobelsdorf, Chief of Staff of the 5th Army, complained to Falkenhayn that if they did not gain ground more quickly, his men would have to be pulled back to their February starting point. Falkenhayn relented and the slaughter continued.

Konstantin von Knobelsdorf

Erich von Falkenhayn

In other news from the west, German domination of the skies above the trenches, established the previous fall, ended around the beginning of April as the Allies caught up in aircraft design and manufacture. On 14 April British planes actually bombed Adrianople and Istanbul, and though one has to doubt that much damage was done, it is a harbinger of the next war. Nearby, the Greek government on 3 April declared that the Serbian troops on Corfu would not be permitted overland passage to Salonika, but the Allies clearly felt the war effort was more important than someone else’s national sovereignty (sound familiar?) and the Serbian Army Headquarters arrived in Salonika on 15 April.

Downed British plane in Istanbul

Early 1916: British Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter

Early 1916: French Nieuport 11

Early 1916: German Halberstadt DII

Of greater concern, at least for the British, on 24 April the Irish Easter Rising began. Four days earlier a disguised German transport had attempted to deliver arms to the rebels but was sunk off the Irish coast, and Roger Casement, the Irish point man in Germany, was delivered to Ireland by a U-boat and promptly arrested. The uprising, centered in Dublin, occurred nevertheless, much to the surprise and confusion of the general Irish population. The rebellion was small and ill-equipped, and the British, despite the demands of the war, crushed it in less than a week, executing the leaders. At least 485 people died, 143 of them British troops and police and 82 rebels; more than half the dead were civilians, mostly killed by the British, who used heavy weaponry. The Irish would have to wait a bit longer for independence.

The Easter Proclamation

Prisoners in Dublin

Roger Casement

Sackville Street, Dublin

On 26 April Britain and Germany concluded an agreement regarding the transfer of wounded prisoners to Switzerland, a rare instance of civil behavior in a war of civilization at its most barbaric. More important to the future, on 29 April the Allies issued the Havre Declaration, which guaranteed the existence and integrity of the Belgian Congo, far and away the most abused and exploited of the African colonies.

As a further – and far more consequential – example of European disregard for self-determination, at least for those who were not White, there is the infamous Sykes-Picot Agreement, which first raises its head in April 1916. On the 26th the French and Russian governments agreed the Turkish provinces in the Near East would after the war be divided up into spheres of influence and colonies for the Allies; the British would join on 9 May. The Agreement involved competing claims between the French and British and of course ignored promises made to the people who actually lived in these neighborhoods, which is why the Agreement was secret, only to be revealed by the Bolsheviks in 1917. A century later we are reaping the whirlwind of Sykes-Picot, especially in the case of the multi-ethnic non-state of Iraq.

François Georges-Picot

Mark Sykes

Meanwhile, in the east the Russians took the key city of Trebizond on 17 April, and to the south the British advance into German East Africa continued with the capture of Kondoa Irangi by General Jacob van Deventer on 19 April. Deventer could not proceed further because his men were exhausted from the grueling march from Moshi, during which he had lost more than 2000 horses. The rainy season was beginning, and Deventer, waiting for Lettow-Vorbeck’s counterattack, was soon cut off from supplies, as roads and bridges were washed out. Oh, the Portuguese got into the war by occupying a small bit of German East Africa on 11 April (take that, Kaiser Bill!).

Jacob van Deventer (seated)

hard to see map

Remember Kut? By April life was becoming very uncomfortable for General Townshend and his boys. The Royal flying Corps was now dropping food and ammunition into the town (and the river and Turkish emplacements), the first air supply attempt in history, which proved as futile as the one a quarter century later at Stalingrad. At the beginning of the month General George Garringe, who had replaced the fired Aylmer in March, started up the Tigris with some 30,000 troops and took Falahiya on the northern bank with heavy losses on 5 April. The next Turkish fortified position was Sannaiyat, about three miles upriver, and the British attacked on 6 April and again on the 9th. The Turks were well entrenched and both attacks were costly failures.

George Garringe

Townshend

Saving Kut

Garringe saw that taking the Sannaiyat trench line would require sapping and consequently take far too long to save the starving garrison at Kut, and he decided to cross to the southern bank. The difficulty was that the rains had begun and the southern bank of the river was already turning into a vast swamp. Despite this, the troops were able to seize the Bait Aissa trenches a few miles upriver from Sanniyat on 18 April, but flooding and mud prevented the British from moving any further. Hoping that the action had drawn Turkish troops from Sanniyat, Gerringe hurried back and assaulted the position for the third time on 22 April and was repulsed.

“For the King-Emperor!”

British at Kut

Turkish lines at Kut

There was a final desperate attempt to aid the troops in Kut. The river steamer HMS Julnar was loaded with 250 tons of food at Basra and sent on a dash up the river on 24 April. Before they reached the blockaded town the steersman was shot, and the steamer grounded on the bank and was captured by the Turks. On 26 April Townshend called for an armistice but negotiations, unsurprisingly, went nowhere. T.E. Lawrence and another were sent from Cairo to attempt to bribe the Turkish commander with £2,000,000, but the Ottoman supreme commander, Enver Pasha, refused, and on the 29th the garrison surrendered.

HMS Julnar before her last journey

HMS Julnar loading troops

The 147 day siege and the rescue attempts had cost the British 30,000 killed and wounded and 13,000 captured; the Turks are thought to have suffered about 10,000 casualties. Of those taken prisoner 70% of the British and 50% of the Indians died in captivity, mostly from disease. The Turks also lost Goltz Pasha, who on 19 April died in Baghdad either from typhus or being poisoned. General Gorringe and General Percy Lake, the other commander of the Mesopotamia army, were both sacked and replaced by General Stanley Maude, who would retrain the army and ultimately take Baghdad.

Stanley Maude

Percy Lake

Golz Pasha in his Field Marshal’s uniform

General Townshend spent the rest of the war in very comfortable captivity on an island in the Sea of Marmara, an object of contempt to the men he had left behind. While it is true that Townshend wanted to retreat from Kut back in December and was overruled by General Nixon, his conduct during the siege was incompetent and contemptible. He never expelled the 6000 inhabitants of Kut or foraged the area around the town for food stocks, and he consistently refused to attempt a break out to meet and aid the relieving forces or even launch diversionary actions to draw off Turkish defenders. He was far more concerned about getting a promotion and caring for his dog (well, I can understand that) than his starving men, whom he never visited in the hospitals. Unlike most of his men he survived the war, but his reputation was shattered and his military career at an end.

After the fall: Indian troops

After the fall: marching into captivity

After the fall: Townshend with Kahlil Pasha

The fall of Kut was certainly a humiliation for the British, especially as it came at the hands of the Turks (Townshend wanted to surrender to Goltz), but it had little effect on the war, even in the east – the Ottomans were at the end of their supply line and could never threaten Basra. A lot of men died, but it was virtually nothing compared to the blood being spilled on the Western Front.

![220px-Pobedata_nad_syrbia[1]](https://qqduckus.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/220px-pobedata_nad_syrbia1.jpg?w=640)