By the beginning of October many, especially on the German side, knew that the war was finished for the Central Powers but the killing would continue for another month while an armistice was negotiated. It was hardly “dulce et decorum” to die for your country when there was absolutely no reason to.

On 2 October the Fifth Battle of Ypres and the Battle of the Saint-Quentin Canal came to an end, and on the 3rd the (ironically named) Battle of the Beaurevoir Line began. The Line was the last string of German trenches, a little more than a mile east of Saint-Quentin, and by 10 October the Americans and French had seized the heights above the Line, marking a 19 mile wide breach of the Hindenburg Line. General Rawlinson on the operation: “Had the Boche not shown marked signs of deterioration during the past month, I should never have contemplated attacking the Hindenburg line. Had it been defended by the Germans of two years ago, it would certainly have been impregnable….”

To the north the Canadians handily won the Second Battle of Cambrai on 8–10 October, capturing a city that was largely destroyed and evacuated by the Germans. The easy victory is understandable: all the pressure on the Hindenburg Line to the south left this sector denuded of troops. The depleted German divisions were severely outnumbered, had few guns, no air cover and no tanks, of which the Allies had 324. The end was becoming clearer and clearer.

On 14 October the Battle of Courtrai (or Battle of Roulers or Second Battle of Belgium) began, and by its end on the 19th Ostend, Lille, Douai, Zeebrugge and Bruges had been recaptured by the British and Belgians. On 20 October the rest of the Belgian coast was recovered.

To the south the Meuse-Argonne Offensive moved into phase two on 4 October. The exhausted American divisions gave way to fresh formations of eager doughboys, who quickly – and frequently recklessly – cleared the Argonne Forest by the end of the month, during which time they advanced 10 miles. At the Battle of Montfaucon 14-17 October the Americans broke the Hindenburg Line at the Kriemhilde Stellung, while on their left the French Fourth Army moved 20 miles and reached the Aisne River. At the onset of Montfaucon legendary American corporal Alvin York singlehandedly captured 132 prisoners, a feat that would have been impossible a year earlier. Phase 3 began on 28 October and would last until the armistice.

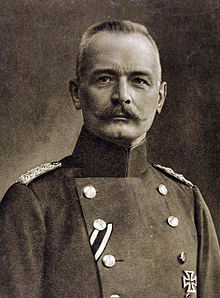

A sign of the impending end: on 27 October Ludendorff, virtual ruler of the German Empire for two years, was asked by the Kaiser to resign, which he did without objection.

A more cataclysmic sign appeared in Italy. On 24 October, the anniversary of the Caporetto disaster, General Armando Diaz finally launched the long awaited offensive against the Austrians with an assault on Monte Grappo, while his main armies prepared to cross the Piave River, which was in flood. The crossing of the swollen river was difficult, but by the 28th the Italians had established several bridgeheads on the northern bank and were advancing. The Austrian commander, Svetozar Boroević von Bojna, promptly ordered a counterattack, but his men refused to obey the order, not a good sign. Svetozar Boroević, known as a defensive expert, ordered a general retreat, and on 30 October the Italians took Vittorio Veneto, a dozen miles north of the Piave.

Aiding the Allies was the simple fact that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was crumbling. On 28 October Bohemia (part of Czechoslovakia) declared its independence, and the following day a group proclaimed the independence of the South Slavs. More crushing, on 31 October the Hungarian Parliament voted for independence, thus ending the Austro-Hungarian state. By the time the Battle of Vittorio Veneto ended on 4 November Austria was out of the war.

Meanwhile, Allied forces were advancing deeper into Serbia, and in the east the British took Tripoli, Homs and Aleppo in Syria and Kirkuk in Mesopotamia from the Turks; the French took Beirut. Far to the east the British took Irkutsk (remember Risk?) on 14 October and Omsk on the 18th, although the whole reason for these operations had essentially disappeared.

Diplomatic notes were flying all over Europe. On 4 October Germany and Austria sent notes to President Wilson requesting an armistice, and four days later Wilson told the Germans that evacuating occupied real estate was the first step. On the 12th the German government agreed, but three days later Wilson set further conditions, including that he deal with a democratic German government, a tough proposition for the Germans. Nevertheless, Wilson agreed to pass the proposal on to the Allied governments.

The Austrians had to wait until 18 October for a noncommittal reply, and on the 27th the Austrian government sent a second note to Wilson and one to Italy requesting an immediate armistice. Meanwhile, the Empire was dissolving. On 16 October a desperate Emperor proclaimed the ancient empire to be a federal state based on national groups, but it was already fragmenting. On 21 October Czechoslovakia declared its independence, and the Ban of Croatia (the traditional local government) proclaimed its support for the Yugoslav National Council. On the 29th the Council rejected the policy of the Empire and declared Yugoslavian independence, which was adopted by the Croatian Congress the next day. Three days earlier the King of Montenegro had announced support for Yugoslavia. On 31 October there were revolutions in Budapest and Vienna, and Hungary withdrew from the union; that same day Emperor Karl I, no longer possessing an Adriatic port, handed his fleet over to the Yugoslavs.

The Ottoman Empire was also collapsing. On 14 October the Turks requested an armistice from President Wilson, and on the 30th an armistice was signed by the Allies and the Turks. Hostilities ended the next day, and Turkey was out of the war and bereft of their Arab empire.

On a smaller scale, on 4 October King Ferdinand of Bulgaria abdicated in favor of his son, who became Boris III. Surprisingly, his throne would actually survive the political cataclysm born of the defeat of the Central Powers.

Turkey, Austria and Bulgaria were all out of the war, and Germany was seriously seeking an armistice. Yet the war and the killing went on as the victors dithered.