(Yes, the maps are hard to read because of the small size, but I have no idea how to make them bigger or create a link to the original. But I will continue to include them – I like maps.)

While the men on the Western Front were quickly learning about industrialized warfare, in the east, where the front ran for almost a thousand miles from the Baltic to the Black Sea, things were a bit different. Because of the difficulty of fortifying and manning such a long line, the war was more fluid, with impressive breakthroughs that the generals in the west kept spending men on but could not achieve. On the other hand, the Russian and Austro-Hungarian armies were far inferior in quality and their communications more primitive, which meant that while penetrating enemy lines was much easier, sustaining any advance was more difficult. Austrian troops would need constant help from the Germans.![WWOne24[1]](https://qqduckus.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/wwone241.jpg?w=640&h=495)

On 12 August Austria invaded Serbia with 270,000 troops, a fraction of their total operational force of some two million, and they faced a poorly equipped Serbian army, whose entire operational strength at the time was about 250,000 men. Nevertheless, despite two more Austrian invasions, by the middle of December virtually nothing had changed – except the loss of men: 170,000 for Serbia, 230,000 for Austria. Even without a static front industrialized warfare did not come cheap.

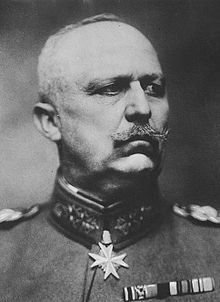

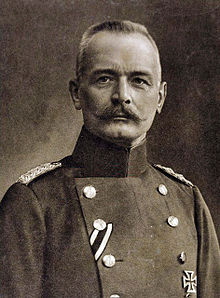

Meanwhile, on 17 August the Russians invaded East Prussia, but the Russian Second Army was annihilated by Field Marshall Paul von Hindenburg at the Battle of Tannenberg from 26 to 30 August; the Russian commander, Alexander Samsonov, shot himself. The engagement actually took place near Allenstein, 19 miles to the east, but as a symbol of revenge for the Polish-Lithuanian defeat of the Teutonic Knights in 1410 it was named after Tannenberg. Hindenburg and his chief of staff, Erich von Ludendorff (who would become virtual dictator of Germany in 1918), then took the Eighth Army east and in the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes from 7 to 14 September destroyed the Russian First Army as well,

despite being heavily outnumbered. Russian troops were driven from German soil and would not return again until late 1944.

The major problem for the Russian army was incompetent and corrupt officers. The individual soldier was tough and at least initially willing to fight for his country, despite its oppressive and brutal government, but he was very badly led and constantly short of supplies. Not only were Russian industry and transportation far less developed than that of her allies and Germany, but selling army supplies was a thriving practice among senior officials and army officers. (One is perhaps reminded of the current Iraqi army.) Further complicating any advance into Germany – and vice versa – was the broader Russian railway gauge, which would plague the Wehrmacht in the next war.

On the other hand, as the Serbian campaigns demonstrate the Austro-Hungarian army was nothing much to write home about either. On 23 August the Austrian First Army met the Russian Fourth Army near Lublin on the border between Russian Poland and Austrian Galicia (parts of modern Poland and Ukraine), inaugurating the Battle of Galicia. The Fourth Army was driven back, as was the Fifth Army immediately to the southeast, but unfortunately for old Franz Joseph, in the southernmost sector of the front the Russians actually had an able commander, Aleksei Brusilov, who broke the Austrian advance. Defeat turned to flight, making the Austrian gains in the north untenable, and when the battle ended on 11 September, the Russian front had advanced a hundred miles to the Carpathian Mountains. The heart of the Austrian army had been ripped out, and the Germans were forced to send troops to Austria’s defense and thus limit their advance into Russian Poland.

A month and a half of war in the east demonstrated what everyone had already suspected: the Germans were good and the Austrians and Russians were not. The Germans had lost 24,000 men, including captured, the Austrians 684,000 and the Russians a 605,000. But the Russians now occupied Galicia, balancing the disaster in the north and perhaps keeping Nicky on his throne a bit longer.

The Russian supreme command was in fact contemplating an invasion of Silesia, which would expose the flanks of the Germans in the north and the Austrians in the south. The Germans got wind of this, and Hindenburg, now supreme commander in the east, sent the Ninth Army under August von Mackensen southeast to forestall the invasion. The Russians countered by ordering the Fifth Army to forget about Silesia and withdraw to the area of Łódź to deal with the threat from von Mackensen, who struck Paul von Rennenkampf’s First Army (yes, he is a Russian) on 11 November. Thus began the Battle of Łódź, which went on until 6 December, when the Germans finally gave up trying to capture the city. The Russians then nevertheless moved east towards Warsaw to establish a new defense line, and Rennenkampf, who had already been accused of incompetence at Tannenberg, was canned. Another 35,000 Germans and 90,000 Russians down the tubes.

On 7 February Hindenburg resumed the offensive with a surprise attack in the midst of a snowstorm and drove the Russians back some seventy miles, inflicting heavy casualties and accepting the surrender of an entire Russian corps. But a Russian counterattack halted the advance, and the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes ended on 22 February with the Germans down 16,200 men and the Russians 200,000. Well, one death is a tragedy, 50,000 is a statistic. More uplifting (if you happened to be a German or an Austrian), on 2 May von Mackensen, now commanding Austrian forces, began an offensive near Gorlice and Tarnów (southeast of Krakow); this was the beginning of a push that would ultimately become known from the Russian point of view as the Great Retreat of 1915.

In other news from the east during the first ten months of the war, on 29 October the weakling Ottoman Empire, seeking to regain territory lost in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, shelled the Black Sea ports of Sevastopol and Theodosia. There had been no declaration of war, and the two warships, recently acquired from Germany, were under the command of German officers, who may have acted on their own. Seeking another front against Russia, the Germans had been putting pressure on Turkey to enter the war and found a willing accomplice in the most powerful man in the Empire, War Minister Ismail Enver, better known as Enver Pasha, who admired the German army. In any case, Russia declared war on 1 November, promptly followed by Serbia and Montenegro, and before the Turks could negotiate Britain and France also declared war on 5 November. In response the titular head of government, Sultan Mehmed V, declared war on Britain, France and Russia, and on 14 November the head sky-pilot of the Empire, the Sheikh ul-Islam, issued a series of fatwas that declared this to be a jihad, a holy war against the infidel enemies. Now the Turks were in on the fun. Only the Italians were missing.