(This is more work than I anticipated.)

All the operations associated with the Ottoman Empire and the German colonies in Africa were certainly peripheral to a victory in Europe; even the campaigns in the Caucasus, while important to the Russians, had little to do with the European war. But they are part of the Great War, and the campaigns in the Middle East would have an impact on the shape of the post-war

On 2 November the Russians made the first move, sending an army into northeastern Turkey, where they had allies in the form of the Armenians, anxious to escape Turkish oppression. The offensive petered out by 16 November, and the following day the Ottoman Third Army counterattacked, driving the Russians back with heavy casualties. By the end of the month the front stabilized some fifteen or so miles into Turkey, but Russian morale was low, while that of the Turks was high. So high, in fact, that Enver Pasha launched his own offensive towards Sarikamish on 22 December, despite objections from military advisors that the winter conditions would make the campaign extremely difficult.

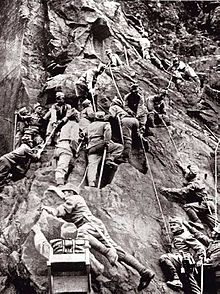

Kurdish cavalry

The Caucasus front

Well, Enver was a far better politician than general, and the Battle of Sarikamish ended on 17 January, a major Turkish defeat. The Turks suffered some 60,000 casualties, the Russians half that, many on both sides freezing to death. Enver gave up generaling and blamed the Armenians for the defeat. On 20 April the Armenian population of Van, fearing massacre, revolted, and the city was besieged by the Turks until May, by which time the Russians had occupied the province of Van; they entered the city on 23 May. The Caucasus front was then relatively quiet until late in the year.

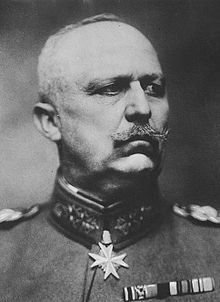

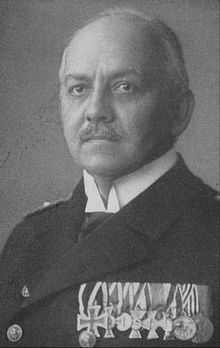

Baron Kress von Kressenstein

For good reason: the British had begun putting pressure on the Empire’s southern provinces and the Dardanelles, drawing Ottoman troops away from the Caucasus. In the far south the Turks decided immediately to attack Egypt, which though nominally a part of the Empire, had been occupied by the British since 1882. On 18 November Baron Friedrich Kress von Kressenstein, one of the clutch of German advisors in Istanbul, was given command of part of the Turkish Fourth Army and began preparations for an advance across Sinai, which the British had evacuated. Since the coast road to Egypt would mean being shelled by the Royal Navy, Kress von Kressenstein had to take his 20,000 troops through the Sinai desert, which he did with little loss of life, no mean feat. The Turkish force reached the Canal on 2 February, and the following day the battle proper began. Some units actually crossed near Ismailia, but 30,000 troops (most of them colonials) and gunboats on the Canal and lakes were too much, and the battle ended on the 4 February with the Ottoman army retreating to Palestine.

Iraq before it was Iraq

The British had meanwhile gone on the offensive, landing a mostly Indian force at Fao on the Shatt-al-Arab in Mesopotamia (Iraq) on 6 November in order to protect the Anglo-Persian Oil Company’s refinery at Abadan, just across the frontier in Iran. The automobile had arrived and more important, navies were switching from coal to oil, and suddenly the Middle Eastern backwater was emerging as a center of imperial attention. On 22 November the Indian Expeditionary Force captured Basra (sound familiar, Americans?) and continued up the river to Qurna at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, where after being surrounded the Ottoman force of a thousand men surrendered on 9 December. The Turks, hard pressed at Gallipoli, did not counterattack until 9 April, when they assaulted the British position at Shaiba, near Basra. The 14,000 Arab and Kurdish irregulars were easily scattered, but it took the 7000 man British garrison two days to defeat the 4000 regular troops. London ordered the local commander, Charles Townshend, to continue advancing up the Tigris.

Prince Mubarak of Kuwait

General Charles Townshend

The British successes in lower Mesopotamia, albeit against weak Turkish forces, enhanced their credibility in the Arab world. Even before the invasion Sheikh Mubarak Al-Sabah, ruler of Kuwait, nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, had sent forces to drive out the small garrisons in southern Mesopotamia, and in return London declared Kuwait an independent state under British “protection.” Arab nationalism had begun to emerge in the previous century, competing with the Pan-Islamism represented by the Ottoman Empire, but demands on Istanbul were still moderate in the early twentieth century. The British Foreign Office understood the value of encouraging local insurgencies once the war started, but the great Arab Revolt would not occur until 1916.

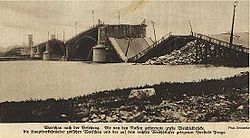

Of greater concern for the Empire was the Allied assault on the Dardanelles, the narrow straights that lead from the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara and through the Bosphorus to the Black Sea. When the Turks entered the war in November, they immediately closed the straights and began to mine them, choking off the major Allied supply route to Russia (the German fleet blocked the Baltic, and Vladivostok might have been the other side of the moon). Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, suggested forcing the straights with a fleet of obsolete warships that were useless against the German navy, thus risking little for huge rewards: Russia could be supplied by sea, Istanbul could be bombarded and the Bulgarians and Greeks, who hated their one-time Ottoman masters, might enter the war.

Admiral John de Robeck

Guess who?

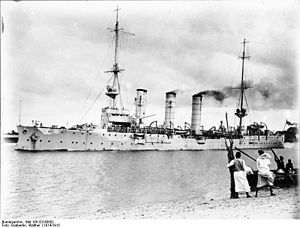

The Dardanelles fleet

On 2 January 1915 Russia, dealing with the Ottoman offensive in the Caucasus, asked the Allies to divert Turkish troops by attacking in the Aegean, and the Dardanelles operation was set in motion. On 19 February the Anglo-French squadron began shelling the forts on both sides of the entrance to the straights and by 25 February had destroyed them and cleared the entrance of mines. The problem was the mobile artillery batteries, which could evade the naval gunfire and attack the minesweepers, but pressed by Churchill Admiral Sackville Carden planned an all-out attack, claiming that the fleet could be at Istanbul in two weeks. Because of illness Carden was replaced by Admiral John de Robeck, and on 18 March eighteen old battleships and a supporting cast of lesser vessels headed up the straights towards the “Narrows,” where most of the forts and minefields were.

(An historical note: some fifteen miles past the Narrows on the European side is a small river called Aegospotomi by the Greeks. It was at this point in the straights in 405 BC that the Spartan Lysander and his Persian-supported Peloponnesian fleet annihilated the last Athenian fleet, bringing about the surrender of Athens the following year and ending the twenty-seven year-long Peloponnesian War.)

The Bouvet

Naval gunnery was able to destroy communications among the forts and take out some guns, but despite ammunition shortages (it was later learned) Turkish fire continued, and the minesweepers, which were crewed by civilians (!), decided the party was over and left. The French battleship Bouvet was the first to strike a mine, capsizing with almost all hands lost; two other French battleships were damaged. Two British battleships were sunk and a third severely damaged, and the fleet retreated to the Aegean. Some of the captains wanted a second shot at the Turks, but de Robeck and important figures in the Admiralty opposed it, and the operation was abandoned.

HMS Irresistible sinking

The Bouvet sinking

That left Plan B, an amphibious assault on the Gallipoli Peninsula, which formed the European bank of the Dardanelles, in order to silence the Turkish guns on the northern bank of the straights with troops. This was a mighty ambitious undertaking, given that no one had ever conducted a landing against opposition with twentieth century weaponry, but the Allies presumed there would be no problem since Turkish soldiers were very poor, a conclusion reached from Turkish losses in the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 and traditional European notions of superiority. Further, British intelligence underestimated the number of defending troops and had only vague ideas concerning the terrain.

Cape Hellas, Gallipoli

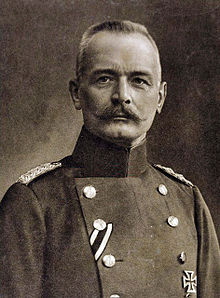

The 78,000 men of the Mediterranean Expedition Force gathered in Egypt, where Imperial troops training for France were organized into the first Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), which would be forever associated with Gallipoli. Novel logistical problems and weather prevented the Expedition, under Sir Ian Hamilton, from reaching Gallipoli until late April, during which time the Turks were able to reinforce their positions and prepare defenses. The Ottoman Fifth Army, some 60,000 men, was put under the command of a German officer, Otto Liman von Sanders, who set up a flexible and mobile defense; one of his division commanders was Mustafa Kemal, later known as Atatürk, who would become the founder of the Turkish Republic.

Mustafa Kemal

Sir Ian Hamilton

Otto Liman von Sanders

On 25 April the main landing commenced at Cape Hellas on the tip of the peninsula, while the Anzacs went ashore some ten miles up the northern shore near Suvla Bay. The landings were relatively unopposed, but a swift counterattack by Kemal pinned the Anzacs on the beach. The main force pushed about two miles inland, but counterattacks drove them back, and by 8 May both fronts were static, replete with the trenches and wire. The Western Front had been recreated on Gallipoli, and Hamilton had already suffered 20,000 casualties. Nothing much more would happen until August, leaving the troops to be worn down by heat, disease and Turkish shelling.

In the trenches at Gallipoli

Gallipoli landing

Off in the west of the Mediterranean the Italians finally got involved. Italy had in fact been allied to the Central Powers, but was lured away by the Allies with promises of territory, notably the southern Tyrol, taken from the Austrians after the war. On 23 May Italy declared war against Austria, despite not being really prepared for warfare in the mountainous terrain against well-fortified Austrian positions (though it should be noted Italy entered the Second World War with less and poorer quality artillery that it did the First). The result would be twelve Battles of the Isonzo River from June 1915 to November 1917.

The Italian front

Meanwhile, Austrian and German foreign possessions were quickly overrun at the outbreak of the war – with the exception of German East Africa (Burundi, Rwanda and part of Tanzania), where the local commander, General Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, would lead the British on a merry chase for the entire war. To conquer the German territory and stop the raiding into British East Africa (Kenya, Uganda, Zanzibar and part of Tanzania) the British brought in Indian troops for a two pronged attack. The German garrison was all of 260 colonial troops (Schutztruppe) and 2472 native levies, the Askari, who proceeded to set the pattern for the next four years. On 3 November 86 mounted Germans and 600 Askaris defeated the northern prong of 1500 Punjabis at the Battle of Kilimanjaro and then raced south to join the Battle of Tanga, where on 4 November Lettow-Vorbeck’s 1000 troops routed the British force of 8000 men. There would be no easy pickings for the British here, and more than 200,000 Indian and South African troops would be kept busy until the end of the war.

German cavalry at Kilimanjaro

Battle of Tanga

Askaris

Genera Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck

East Africa

Finally, two ominous incidents occurred during these first ten months of the war. On 7 May the German submarine U-20 sank the liner RMS Lusitania (which was carrying small arms munitions), killing 128 Americans, and this, together with the dramatically inflated atrocity stories about Belgium, began swaying American opinion against Germany. Berlin made the case that a surfaced submarine was easy prey for an armed merchant vessel and had publically warned Americans about traveling to Britain, but in response to a warning from President Woodrow Wilson submarines were directed to steer clear of passenger liners.

U-20 (second from left)

RMS Lusitania

And on 27 May the Turkish Minster of the Interior ordered all Armenians deported from Ottoman territory, and the killing began. Yes, President Erdoğan, there was an Armenian Genocide.

![WWOne24[1]](https://qqduckus.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/wwone241.jpg?w=640&h=495)