(This piece is being published again in order that the participants at my talk on alternative history can read the full text on the alternate Alexander; a new post will take its place in a week or so. The names in bold type are historical characters; for clarity the Greeks are given their original royal cognomina, though they do not apply in this history. Alexander’s son, born after his death, was named Alexander [IV]; here is named Philip [III].)

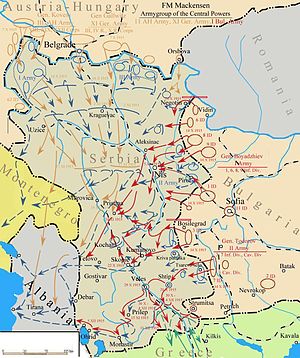

Our boy in fighting trim

……..Once the fever had passed, Alexander’s first act was to order the construction in Babylon of a massive new temple of Marduk, whom he believed had saved his life. He then dispatched Craterus to take over the governorship of Macedon and Greece from the aging Antipater and made further arrangements for the training of 20,000 Persian youths brought west by Peucestas. The already planned expedition to circumnavigate Arabia then got underway, with the King accompanying the fleet, which would keep the land forces supplied. But the heat was debilitating, especially for the army, and it rapidly became more difficult to gather food and even water. Reaching the point where the Arabian Peninsula turns south and west and getting a better idea of just how big Arabia was, Alexander created a smaller squadron of ships, provided them with all the supplies that could be spared and sent them on. He meanwhile led the remaining forces back to Babylon, a march that many said outdid the Gedrosia in hardship.

Babylon

Alexander and Craterus in their younger days

Roxane and with her son Philip

Back in the capital the King was pleased to discover that his Bactrian wife, Roxane, had delivered a boy, whom he named Philip after his father, to the delight of the older Macedonian veterans, who were unenthusiastic about Alexander’s Asian ways. He attended to the administration of the Empire and the training of the new Greco-Persian units, one of those Asian programs so disliked by his soldiers. Towards the end of the year he traveled to the Phoenician coast to inspect the new fleet being assembled in the Mediterranean, then spent the winter in Alexandria, indulging himself in ordering new temples built around the Hellenic world, including a splendid monument to his father in the ancestral Temenid royal burial grounds in Aegae.

The royal tombs at Aegae

In the spring of 322 Alexander got word that his tutor, Aristotle, had died, and he ordered a period of mourning throughout the Greek world. He also dispatched a squadron of ships south in the Red Sea to meet the expedition coming from the east and spent most of the year mustering forces and supplies for a march west along the African coast. The Greek cities in Sicily, which had congratulated him on his return from the east, were now beginning to make dire predictions of what threats would emerge should the Carthaginians seize the entire island and consolidate their position there. The King, who had always wanted to bring all the Greeks into the Empire, agreed and began preparations for an expedition against Carthage. Meanwhile, Craterus was compelled to take an army north to deal with the Paeonian tribes that had renewed their traditional raiding south into Macedon.

Alexandria (Egypt)

The African army began its march westwards in the spring of 321. The coastal towns of Cyrene had submitted to Alexander when he entered Egypt a decade earlier, but the heat and constant need to feed and water his forces without devastating the area’s inhabitants meant fairly slow progress. At the site of modern Benghazi the King left a force to build yet another Alexandria and continued westward along the coast with the bulk of the army and navy, driving into the territory of tribes nominally allied to Carthage. Sandstorms and constant harassment by the desert tribes, who seemed to spring out of nowhere, slowed progress greatly, however, and with growing supply problems Alexander decided to turn back and winter at the new Alexandria Kyrenaea. The western desert had proved a much greater challenge than the Sinai had back in 332.

During the winter the King learned that the fleet sent around Arabia had sailed up the Red Sea to Egypt, and he ordered that bases be established along the route to facilitate trade. He had been sending out mounted units to reconnoiter the African coast, especially regarding water supplies, and contact the tribes along the route. With the treasure of the old Persian Empire at his disposal buying the Libyans away from Carthage was easily done, and when the army was ready to march in the spring, he sent to the Punic capital demanding an alliance and the evacuation of their troops from Sicily. Their answer, delivered a few weeks later, was a surprise raid on Alexander’s fleet, during which his transports suffered heavy damage and his Phoenician crews revealed an extreme reluctance to attack their Punic cousins.

A rooky trireme going into battle with its masts still up

Triremes under sail

Sending the Phoenicians back to Alexandria with instructions that new crews and more warships and transports were to join him as soon as possible, Alexander characteristically moved quickly, trusting his new Libyan allies to provide information about the enemy and the land. By summer’s end he had reached Lepcis Magna, well into Carthaginian territory. The extremes of heat and cold had once more taken a toll on his army, and he decided to rest here where supplies were plentiful and await the reinforcements coming by sea. Soon enough the Carthaginian navy reappeared, this time in greater numbers, and Alexander was forced to beach his supply vessels and guard them with troops while his outnumbered and out rowed warships were so roughly handled that they were soon fleeing and heading for the shore. The enemy fleet departed, and the next day the King sent the surviving naval units east to meet the reinforcements and continued the march to Carthage. Despite the naval defeat morale was high, since the men knew that if the King could take an army though the Hindu Kush, he could certainly traverse this region.

A week’s march from Carthage his way was blocked by the enemy army at Bararus. The force was larger than his and composed of Libyans and mercenaries, most of them veterans from the Carthage’s Sicilian campaigns, and cavalry from Numidia. Ptolemy Soter suggested that the King simply buy the army from its Carthaginian leaders, but he replied “I will not purchase a victory.” While some of the King’s newly raised units performed poorly and his smaller cavalry force had a time of it with the Numidians, his Macedonians and Greeks broke through the enemy center, at which point the Numidians fled and the subject and mercenary infantry surrendered. Alexander promptly hired the mercenaries and gave the Libyans the option, eagerly taken, of joining his army.

Ptolemy Soter

Within a month Carthage and the other Punic towns had surrendered. Knowing that he could not yet deal with their navy, Alexander had offered terms that left the Carthaginians in possession of their emporia, excepting in Sicily, and their commercial empire, but they were bound in an alliance. They in turn supplied ships to transport Alexander’s disabled troops east and to find his long overdue fleet, which in fact had turned back due to storms. He meanwhile continued west to accept the surrender and alliance of the Numidian king, who agreed to supply cavalry to the King’s army. Taken once more by his pothos, his “longing,” which had compelled him to cross the Danube and the Gedrosia desert, Alexander wished to continue on to the Pillars of Heracles, named after his ancestor, but Ptolemy and the other Companions managed to convince him that after three years on the march he needed to return to the heart of the Empire.

The Pillars of Heracles

In 317 Alexander was back in Babylon, once more replacing failed governors, as he had in 324 upon his return from the east. Later in the year he returned to Pella for the first time in seventeen years, there to meet his mother, Olympias, and host massive banquets celebrating the Macedonian achievement. He also celebrated by taking a small army into Illyria, which had been conspiring with the Dardani to invade northern Macedon. Completely surprised, the Illyrians were easily defeated, and the King established a chain of fortresses to watch over them. The following year he took a larger force north and was joined by several Thracian tribes eager to benefit from the campaign against the Dardani and Triballi, who were duly crushed and scattered. More territory was awarded to the Thracians, and Alexander settled old veterans in a new city on the Danube, Alexandria Istria.

Ruins of Pella

Ruins of Pella

The Queen Mother Olympias

The King decided in 315 to begin preparing an expedition to settle affairs in Sicily, where the removal of the Carthaginian menace had led to a destructive free-for-all among the Greek cities, Syracuse leading the way as the strongest player. A new fleet was ordered from the Phoenicians and the Athenians, who were reminded of the humiliation they had suffered at the hands of Syracuse a century earlier during the Sicilian expedition, and Alexander himself attended to training a younger generation of Macedonians and Greeks. Late in the year, however, word of trouble in India finally reached the west. An Indian adventurer, Chandragupta, having established himself along the Ganges, had engineered revolts in the northern Indus valley and was pressing Alexander’s one time foe and now ally Porus. Engaged in the preparations for Sicily, Alexander dispatched his Companion Seleucus Nicator with a largely Asiatic force with a strong contingent of Greek mercenaries.

Seleucus Nicator

Porus surrendering to Alexander back in the day

Chandragupta

Having intimidated the Italian Greek cities of Tarentum, Croton and Rhegium into alliance, in 314 Alexander, recovered from another bout of malaria, invaded Sicily, where Syracuse under the tyrant Agathocles had formed a coalition of Sicilian cities to resist the invasion. By 312 he had defeated several Greek armies and gained the entire island except Syracuse, which was put under siege. It took almost a year to take the city, after which Alexander organized the Sicilian cities into a confederation similar to that of the Greek cities in Asia Minor. Now, most all the Greeks, except those in Italy, were under Macedonian control, and Alexander began planning an incursion into Italy, where the fledgling Roman Republic was still dealing with the Samnites in the central highlands. Alexander of course saw this as another step in his dream of reaching the Pillars of Heracles.

Agathocles the tyrant

Ruins of Syracuse

Late in 311, however, the King learned that Seleucus had been unable to stop Chandragupta, whose forces were pressing Porus and threatening to seize the passes west into Afghanistan. Alexander determined, with no little enthusiasm, that it was time for him to return to India. The Macedonian-Greek forces destined for Italy instead moved to Babylon, where they were joined by newly raised Asiatic troops. The army spent the winter of 309/308 in Ecbatana, where Alexander discovered that the Scythians had poured across the Jaxartes and were plundering Sogdiania and Bactria. In the spring the King moved into these provinces and after months of pursuit finally drove the major Scythian force into a battle, where it was annihilated. He wintered in Kabul, where he was joined by Seleucus and the remnants of his army and informed that Porus had sided with Chandragupta. In 307 Alexander moved east, dividing the army into three contingents, as he had done almost two decades before. Debouching into the north Indus watershed, he once again faced Porus, who was once again defeated. This time, however, the Indian prince was sent west under guard, and the area was placed under the control of Seleucus, who was left with a substantial garrison of Greek mercenaries.

Once more Alexander built a flotilla and proceeded down the Indus, meeting Chandragupta’s huge army not far south of Porus’ kingdom. Thinking wistfully of the battles against the last Persian king, Darius III, the King took on an Indian army at least twice the size of his own and as at Gaugamela won a crushing victory. And once again the leader escaped, fleeing eastward. Alexander repeated his journey down the Indus, reestablishing garrisons in the major towns, and then followed the route west taken by Craterus years before. In 304 he was back in Babylon, where the news was uniformly bad.

He learned that two years earlier Antipater’s son Cassander had procured the assassination of Craterus and proclaimed Philip Arrhidaeus, the halfwit son of Alexander’s father, king of Macedon, asserting his pure Macedonian blood in contrast to Alexander’s son, who was only one quarter Macedonian. The King’s most able governor in Asia Minor, Antigonus Monopthalmos, had promptly marshaled his forces and marched on Europe, where he defeated and killed Cassander in a particularly bloody battle and having little choice, had the pathetic figure of Arrhidaeus executed. The King’s position in Macedon had been restored, but his long absence in the east and the coup in Macedon had led to the revolt of Syracuse and Carthage, which had regained its Sicilian fortress of Lilybaeum.

Antipater

Cassander

Philip Arrhidaeus

Antigonus Monopthalmos

Alexander immediately moved to Pella, where he found that Cassander had executed his mother, Olympias. Overwhelmed by grief and anger dwarfing that following the death of Hephaestion in 324, Alexander killed everyone even remotely associated with Cassander and then took an army northeast to slaughter every barbarian he could lay his hands on. In 299 he invaded Sicily a second time, this time accompanied by his son, and after another siege captured Syracuse again in 298, this time to make the streets run with blood, seemingly a sacrifice to his mother. Carthage was next, and while an army marched from Alexandria, the King landed his Sicilian army to the west of Utica, his warships, led by the Rhodians, fending off attacks by the Punic navy. A Carthaginian army of Greek and Italian mercenaries was easily defeated, and united with the force from Alexandria, he besieged the Punic capital. It took the almost two years to take the city, and the final assault would be long remembered, as Alexander was treated to a stiff dose of Semitic fury. The devastated city was settled with Greeks and renamed Alexandria Hesperia.

Ruins of Carthage

It was now 295 and Alexander returned to Babylon to spend two years dealing with administrative problems and inspecting the new facilities being built at the head of the Persian Gulf. In 292 he dispatched his son Philip to occupy Kolchis and the southeastern shore of the Black Sea, while he traveled to Alexandria to attend to affairs in the “second capital.” The following year he again prepared for the invasion of southern Italy, moving his fleet and army to Epirus. He assembled a force of some 35,000 infantry and 3000 cavalry while making contact with the Samnites, the Greek cities in the south and the Gallic tribes settled in the Po valley. In 290 the expedition crossed the Adriatic with no opposition and landed at Tarentum, which had agreed to an alliance on the promise of new territory. Other Greek cities joined, seeking aid against the local Italic tribes, the Lucanians and Bruttians, and the King and received word that the Senones and Boii were preparing to cross the Appenines, but chastised by the just concluded war with Rome, very few Samnite communities revolted. The fleet went on to Messana to ferry a Sicilian Greek army to the mainland.

The Senate meanwhile had been negotiating with the Lucanians and Bruttians, offering them new lands to be taken from their traditional Greek foes, while Samnite loyalty was buttressed with promises of land in Apulia. Two legions and allies under the consul P. Cornelius Rufinus were sent north to overawe the Etruscan towns and join a Ligurian army hoping to acquire land from the Senones. His colleague, M’. Curius Dentatus, raced south along the Appian Way with two more legions, picking up some Samnite units along the way. A fifth, understrength legion was hastily raised and sent south along the coast to make contact with the Lucanians.

Dentatus telling the Samnites to shove it

In the north Rufinus marched to Arretium, which was being besieged by an army of Senones, which was obliterated in a set battle outside the city walls. Intimidated, the Boii hesitated, only to be overrun by the Ligurians moving east into their lands. Establishing a few key garrisons and leaving the Ligurians to sort things out, Rufinus headed back south. Almost 500 miles to the south the King moved his army to Thurii to confront a Lucanian horde converging on that city and defeated it with ease at the Battle of the Sybaris River, leading the major Bruttian tribes to open negotiations with him. Using his mercenaries as garrison troops and taking the meager forces of his Italian Greek allies, Alexander then began the march up the recently extended Appian Way, awed by the Roman engineering. To his surprise he learned that Dentatus had already passed Maleventum on his way to the Roman colony of Venusia. Leaving his Greek allies to straggle, he undertook the kind of forced march that had surprised Thebes forty-five years earlier, but he himself was surprised to find Dentatus and his army encamped south of the city. Never had he encountered a foe who could move as fast as he. Further surprise came when the consul refused to withdraw into the city though outnumbered by as much as a third. The resulting Battle of Venusia was a victory for Alexander, but while the legions could make little headway against his phalanx, they seriously cut up his Greek infantry before being flanked by his cavalry. Dentatus lost his life, and less than half his men made it into Venusia, which refused to surrender. With winter coming on the King returned to Tarentum and sent his son back to Macedon to gather more troops.

Venusia

Via Appia

Appian Way

The following year Alexander sent the Sicilians up the western coast, while he again traveled the Appian Way, his army augmented by replacements from the east. Harassed constantly by bands of Lucanians, the Greeks met the now reinforced legion from Rome near Paestum and despite the presence of Macedonian officers were roughly handled and headed back south. The defenses of Venusia had been strengthened, and leaving a covering force, the King marched on Maleventum, where a gate was betrayed and the Roman garrison massacred. Continuing towards Capua, Alexander ran into three legions under the consul M. Valerius Maximus Corvinus, and the Battle of Caudium was fought. This time the Senate had dispatched all the cavalry they could find, but though holding out longer and actually damaging the phalanx, the Romans were sent reeling back to Capua, which the King prepared to besiege. The Senate began discussing negotiation, but the blindold censor Appius Claudius Caecus shamed them with his outrage that they dare talk peace while an enemy was still on Roman soil.

Appius Claudius chastising the Senate

Maleventum

Caudium

Meanwhile, Alexander discovered that the other consul, Q. Caedicius Noctua, was approaching Venusia with two legions from Apulia, and abandoning the siege of Capua, he rushed south to deal with the threat to his communications, passing Venusia before Noctua arrived. With his army damaged by two major battles, facing yet another Roman force and worse, learning of troubles in Asia, he made the hardest decision of his impetuous life and sent envoys to Rome. Exhausted, the Romans agreed to stay out of Sicily in return for the King’s evacuation of Italy. Alexander returned to Macedon, and the following year on his way through Thrace he succumbed to a heart attack at the age of 68.

Roman legions vs. Macedonian phalanx

The world held its breath, and Philip III succeeded his father as ruler of the oikoumene, the Greek-speaking world. The body was taken to Aegae, where the tribute of an Empire reaching from Numidia to India was spent to inter Macedon’s greatest king. Across this vast landscape Macedonian soldiers wept as they received the news of his death and consoled themselves with the thought that he was now a god, looking down upon them from the heights of Olympus. The greatest hero since Achilles was dead.

But not everyone grieved, and the new King was immediately faced with revolts from Sicily to the far east. Philip sent Antigonus’ son Demetrius Poliorcetes to deal with Sicily, while he moved east to deal with revolts by his governors in Media and Bactria and reached the Iranian plateau in 285. Media was easily pacified, but there he encountered Greek troops fleeing the occupation of the Indus valley by Chandragupta and learned that Seleucus had been killed. The King made a momentous decision and sent envoys to recognize Chandragupta’s conquest and Bactrian independence, deciding to withdraw the frontiers of the Empire west to a line from the Caspian Gates south along the eastern border of Persis. Seleucus’ son Antiochus Soter, was made viceroy of the entire Persian heartland.

Antiochus Soter

Demetrius Poliorcetes

Back in Babylon in 283 Philip decided to move the capital to Alexandria and ordered the Old Royal Road west of Babylon refurbished and a spur built south to Egypt. With the Empire momentarily at peace he turned to domestic activities, especially Hellenization, and began a program of encouraging poorer Greeks to settle in western Asia, particularly Syria-Palestine and along the route to Babylon. Because of continued Macedonian resistance, his father’s experiment with joint Greco-Iranian units was abandoned, and Asian troops were henceforth used almost exclusively in the east. Despite calls by his more aggressive generals to revive the Italian campaign, the King decided to postpone it in favor of more consolidation. Then suddenly he was dead, killed when thrown from his horse in 280.

The heir, Alexander IV, was still in his early teens, and Ptolemy Philadelphos, son of the Alexander’s Companion of the same name, was established as Regent. Until his death in 262 Ptolemy continued to advise the King, even after he achieved his majority, but Alexander was not cut from the same cloth as his predecessors and fell into a life of indolence, the court filling with sycophants. The administration of the Empire fell upon the shoulders of its governors and viceroys, who began passing their power on to their own sons. Revolts, all stirred by Greek and Macedonian adventurers, were successfully suppressed with little direction from Alexandria. In 263 the viceroy in Macedon, Demetrius’ son Antigonus Gonatus, having spent the later 260s smashing Gauls on both sides of the Danube, foolishly decided to expand his power by “liberating” the Greek cities in Italy, which had by now fallen under Roman control. Experienced only in fighting barbarians, however, his poorly led army was twice defeated by the Roman legions, and the enterprise was abandoned. Intimidated by the Macedonian fleet in the Adriatic, Rome was content with repelling the invasion, but was now clearly eyeing Sicily, whose garrisons were beefed up by Antigonus.

Antigonus Gonatus

Ptolemy Philadelphos

Alexander died in 248 and was succeeded by his son Perdiccas III, who after three years of incompetent rule was assassinated, perhaps by his younger brother, who succeeded him as Philip IV. Philip is generally considered the last of the great Temenid kings, and during his long reign the Empire was as united as it ever would be. While he confirmed the position of many of the governors inherited from his brother, he attempted to regain control of the offices, fearing any long tenure of power could provide a dangerous local power base. Unfortunately, that was already the case in Macedon and Babylonia, and for all his ruthlessness Philip hesitated plunging the Empire into civil war and tolerated the powerful Antigonid and Seleucid families. He signed a treaty with Rome delineating spheres of influence: Spain and Gaul, where the Romans already had colonies, would be off limits to the Empire, and while both parties were free to send raids into the area north of the Alps and the Adriatic, neither could establish any permanent facilities. Apart from punishing various barbarians off the northern and eastern frontiers and an expedition up the Nile, he refrained from serious military operations and oddly, patronized the arts.

Incredibly, Philip ruled until 199, dying at the age of 80, still loved and feared by his subjects. He had outlived all his sons, and a nephew took the throne as Alexander V. Trouble began almost immediately. In Pella Philip, grandson of Antigonus Gonatus, contested the succession, asserting that the Macedonian troops did not accept Alexander, and in 198 he began moving forces into Asia Minor, replacing the local governors with his own men. Alexander mustered what forces he could and moved north to bar the Cilician Gates, summoning Antiochus Megas, great great grandson of Seleucus, from the east, where he was embroiled with the troublesome Parthians. Fortunately for the King, whose hastily collected forces would have serious trouble facing Philip, the Illyrians, quiet for several generations, poured into Macedon and more threatening, Syracuse was said to have appealed to Rome for liberation from the Macedonian yoke. Leaving what forces he could, Philip rushed back west and sent his fleet back from the Aegean to Sicily to block any attempt by the Romans to cross to the island.

Antiochus Megas

Philip

Coming west, Antiochus affirmed his loyalty to the King, if only to see the rival Antigonids crushed, and 197 was spent clearing Asia Minor and raising new troops. The following year Alexander invaded Europe, while Antiochus returned to the east to deal with a Parthian invasion of Media through the Caspian Gates. The Illyrians had been subdued, but now outmatched by the King, Philip retreated into the Macedonian highlands and offered the Gauls land in Thrace if they aided his cause. This caused the Thracian tribes to enthusiastically support the King, and soon Philip’s Macedonians were deserting in ever increasing numbers. He fled to Italy and sought asylum with the Romans.

Alexander spent two more years in the ancestral homeland and the lands to the north, repairing the damage done by Philip and executing every member of the Antigonid family he could get his hands on. In early 193 came news of a usurper in Alexandria claiming to be a surviving son of King Philip and raising an army, his funds most likely supplied by Antiochus, now surnamed Parthicus. The following year the King easily defeated the usurper, who had been unable to secure Gaza and had remained in the Delta, but he was killed in the battle under suspicious circumstances. Alexander’s youngest son, still a boy, was proclaimed King as Alexander VI by the Macedonians in the army, while his eldest brother, serving as viceroy in Pella, was elevated as Philip V by his Macedonians and immediately began collecting an army. With a promise of autonomy he recruited Alexandria Hesperia and Numidia to his side, raised troops in Sicily and sent several delegations to the Parthians.

Antiochus collected his forces from his eastern frontier and marched toward Anatolia, while Philip secured the Ionian cities and cleared the Cilician Gates. Remembering the destruction of Carthage, the Phoenician cities declared for Antiochus, who had reached the upper Euphrates by 190. But the grand battle never materialized. From east and west came the news: the Parthians were swarming into Media and the Romans had invaded Sicily. Antiochus agreed to recognize Philip as the true King, and Philip in turn formally ceded all the territory east of the Euphrates to Antiochus and guaranteed his right to recruit from the Greek cities. King Antiochus I returned home to face the Parthians, the Phoenician cities submitted and Philip’s boy king brother was dead by the time his men reached Alexandria. Philip took his army back to Macedon, where he confirmed that the Romans, never very good at siege craft, were bogged down before the walls of Syracuse. Ignoring the lessons of a century earlier, he began assembling in Macedon forces from all over the Empire and demanded that Rome evacuate Sicily or face war. Delighted with being presented a casus belli and opportunity to deal with the threat across the Adriatic, the Romans declared war.

The invasion came in 187, after Rome spent the previous year securing its position in Sicily and dealing with problems in the Po valley. A new Roman fleet with new boarding tactics cleared the way across the Adriatic, and four legions were shipped to Greece. It took the Romans almost three years to break into Macedon, and there they met Philip at Dion in the biggest battle ever fought: P. Claudius Pulcher and L. Porcius Licinus led more than 40,000 men against Philip’s 55,000. By nightfall Philip and his Companions lay dead on the field, along with perhaps 25,000 Greeks and Romans. The King’s eldest son, now Alexander VI, fled with his remaining troops to Anatolia, where a number of revolts had erupted. The Romans declared the Greeks free and placed the exiled Philip on the Macedonian throne. The Empire had lost the homeland and all its European possessions.

The dynasty began a downward spiral. Alexander was assassinated in 183 while on campaign in Cappadocia, to be followed by Alexander VII, Perdiccas IV and Alexander VIII in scarcely two decades. Although the Romans kept Philip and his successor Perseus on a short leash during this period, a Gallic invasion of Anatolia and internal revolts, some prompted by Rome, were chipping away at the Empire. Adding to the troubles were the Seleucids, who seized control of Syria-Palestine when they were finally driven from Mesopotamia by the Parthians. By the middle of the century the Alexandrine Empire, once stretching from Numidia to the Indus, had been reduced to Lower Egypt, Cyrene and the fortress of Gaza and under the child King Philip VI was being governed by a constantly scheming coterie of advisors. Prematurely aged from his sybaritic life, Philip died suddenly in 132 and a nephew was elevated as Alexander XII. Within the year he was dead, the victim of a coup launched by a Sicilian Greek mercenary, who promptly proclaimed himself Sosistratus I, ruler of Egypt. The ancient Temenid dynasty was at an end.

Perseus

In the century following the demise of Alexander the Great’s Empire the Romans slowly moved into the lands of the oikoumene, ending the second Antigonid dynasty in Macedon when its kings refused to stop meddling in Greece and then occupying Anatolia and Syria in order to prevent the Parthians from doing so. Thus, the Romans became rulers of the Hellenic world, and while the Alexandrine Empire had disappeared, the work of the Temenid kings in Hellenizing Anatolia, Syria-Palestine and Lower Egypt remained. The urban centers and even some of the rural populations of these regions were thoroughly Greek; even the curious and obstinate Judeans, having lost the most fanatic zealots of their invisible god in a failed revolt, were Hellenized. The Romans would preserve this inheritance for another half millennium and pass it on to Europe.

Finally, there has long been speculation about the course of Western history had Alexander the Great conquered Rome. The destruction of Roman power would certainly have left Hellenism dominant in the Mediterranean, but there is little reason to believe, given the history of the post-Alexander III oikoumene, that a Greek Mediterranean could produce the long-term stability that allowed the Roman Republic/Empire to establish classical civilization so well in western Europe that its core could survive the devastation of the barbarian migrations. And in any case, it was essentially Hellenic civilization that was passed on by Rome.

What a guy!

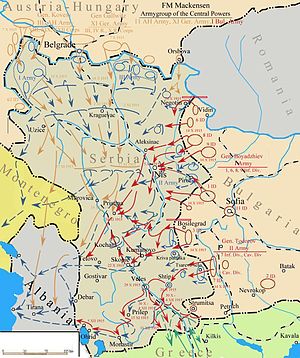

![220px-Pobedata_nad_syrbia[1]](https://qqduckus.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/220px-pobedata_nad_syrbia1.jpg?w=640)